Kirili in Dialogue with

Julio González

Julio González with Dona davant l'espill (Femme au miroir), 1936-1937, Institut Valencià d'Art Modern

“The verticality of Giacometti and Barnett Newman, the contrasts of tradition between Julio González and David Smith are one of the explanations of my work.”

Alain Kirili, New York, 1989

Lighting the fuse, after the appropriation, 1989.

Image legend : “Lévitation II, 2002-3 in front of Julio González's self-portrait: the fact that he is looking at the work is a sign of hospitality.” Alain Kirili

Julio González

des sculptures trouées

by Alain Kirili

published in Artpress, 1979

Artpress’ publication Julio González, des sculptures trouées, by Alain Kirili, 1979

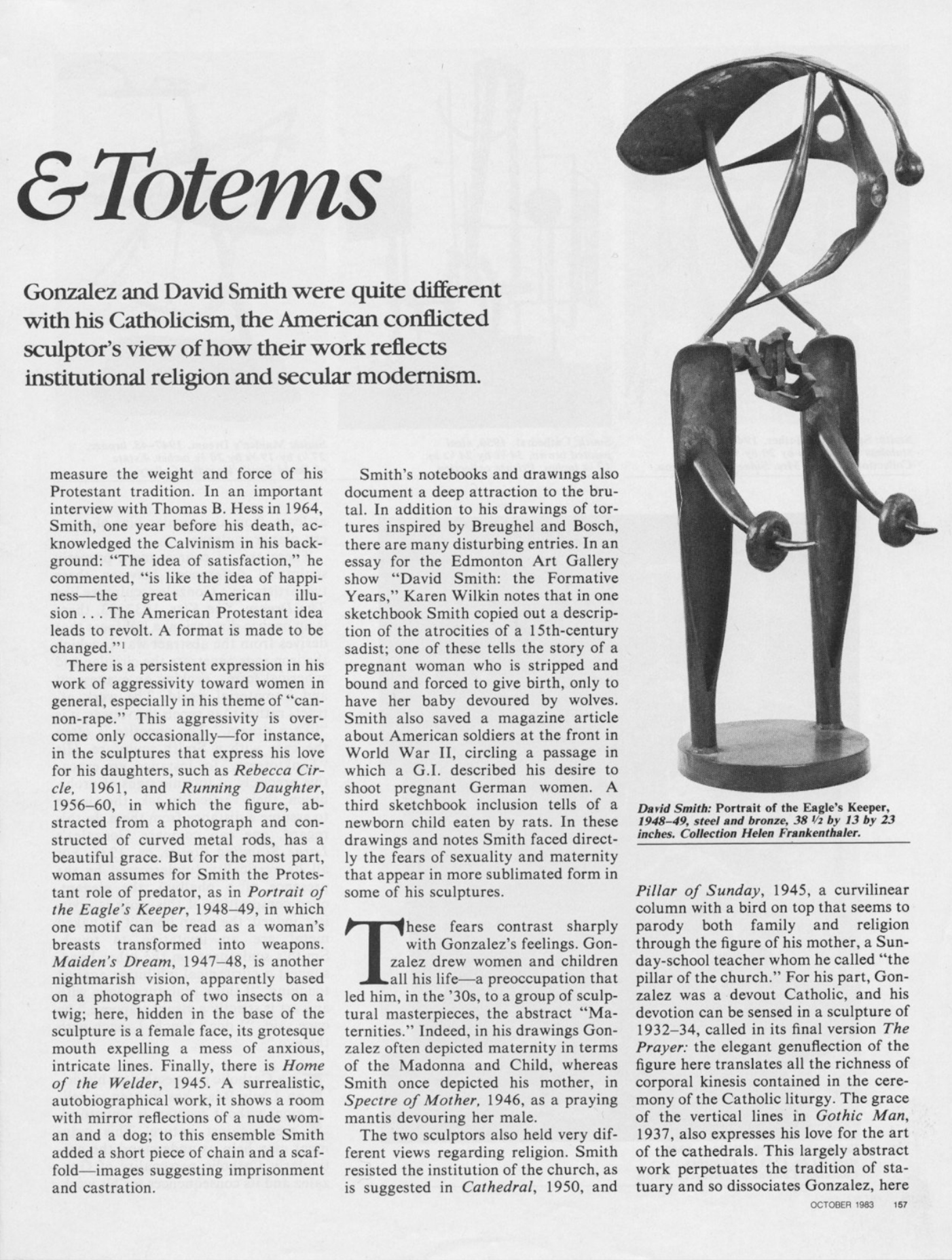

Virgins & Totems

by Alain Kirili

published in Art in America, 1983

In 2003 , Alain Kirili is invited by Kosme de Baranano, director of IVAM, to exhibit in dialogue with works of Julio González at IVAM Valencia. The resulting exhibition is “Alain Kirili Homenaje a Julio González”.

Alain Kirili : Homenaje a Julio González

Designed by the French sculptor Alain Kirili (Paris, 1946), the aim of this exhibition is to review the collection of Julio González and at the same time establish a dialogue between the pieces by both artists. We present seventeen sculptures and four drawings by Alain Kirili in communion with a selection of works by Julio González made by the French artist himself.

After his training in European and US art through the collections of the great American museums, Alain Kirili writes texts about the theory and practice of art, influenced by his association with the Tel Quel group from Paris. In 1972 he makes his first sculptures in zinc, iron and terracotta, and he often uses different combinations of mixed media. Later his interest centres on iron and the forge, when he experiments with this technique in Florian Unterrainer’s workshop. His work shares in the spirit of Post-Minimalism with an absence of volumes, filiform lines and plays of balance. Kirili is an admirer of González and David Smith, both of whom have a great influence on his works in iron.

Alain Kirili’s sculpture is characterised by the renovation of traditional media and materials such as terracotta, cast iron, painted plaster or bronze, and he transforms contemporary materials like aluminium and resin. The diversity of media and the spiritual dimension of his creation are also characteristic features of his work, an example of which are his collaborations with American jazz musicians in his installations. Alain Kirili’s work forms part of the permanent collection of prestigious institutions, and he has been commissioned to make several public pieces, among which are his sculptures in the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris and the Abbaye de Montmajour. Since 1975, his work has been shown in many collective and solo exhibitions both in Europe and in the United States. The great originality of this exhibition resides in the dialogue and the confrontation established between Kirili’s works and Julio González’s art, and more specifically in their work in iron.

Alain Kirili, Commandement , 1990

“ Commandment (Commandment, 1990). Biblical writing responds to the spirituality of Tête à l'auréole (Head with Halo). The other reliefs, Roberta au soleil (Roberta in the Sunshine) and Petit masque baroque (Little Baroque Mask) are concentrations of energy to which the elements in Commandement respond.”

Alain Kirili

Alain Kirili, King, 1986 with drawing Tête avec piquants, 1939,

and sculptures Monsieur cactus (Homme cactus I),1939 and Madame cactus (Homme Cactus II) , 1939 from Julio González

Alain Kirili, Levitation I, 2003 (front)

Julio González, Femme au miroir, 1936-7 (back)

Alain Kirili, Stare, 1983 (left)

Julio González, Daphne, 1937 (right)

“I am delighted to see again Femme au miroir (Woman at the Mirror, 1936-37), who, on my recommendation, was taken of her pedestal in order to be caught red-handed in her delightfully narcissistic pose. A film will show how her bust can twist 180 degrees with a metallic movement to look at herself in the mirror. I myself would make it twist the same way as 25 years ago when I discovered her secret in the collection of Carmen Jiménez and Viviane Griminger.”

Alain Kirili

Julio González

Touched by Grace

by Alain Kirili

published in the catalogue of the Exhibition

“Alain Kirili: Hommage to Julio González,” IVAM, Spain, 2002

Julio González's work has always accompanied me.

I have written about his sculpture and I purchased four drawings, which I hung over our bed. The drawing of a Maternité à l'Enfant, à la Croix (Mother with Child, at the Cross) always evokes in me the religious feeling in art: "Creation is a prayer," Matisse said. In New York, that drawing acted as an antidote against a society that lives on Reformation ethic and for which art is secular or metaphysical. González is at the opposite pole of this tradition. He expresses himself in the great art of incarnation, by means of the body. He creates a sculpture that becomes a living body, never an object or a concept. In his political commitment, he grants a spiritual aura to the Montserrat rebellion. His sculpture is tinged with grace: La Prière (The Prayer, 1935), Maternité (Maternity, 1934), Petite Danseuse (Little Dancing Girl, 1934), Femme à la corbeille (Woman with Basket, 1934), Homme gothique (Gothic Man, 1937)…

The filiform sculptures, Femme à la corbeille, Danseuse eveillée (Wakeful Dancer), Maternité, are iron drawings in space, sculpted out of lightness. A challenge to gravity. Femininity shines forth from his work: his devotion to the Virgin of Catalonia is an inseparable part of his identity that favours this irradiation. A womanless society annihilates me. My creed is: González forever!

All our era, on both sides of the Atlantic, has developed a taste for mockery and negativity: it is the integrism of our intellectual milieu. We live in a world searching for the pulsion of death. González is indifferent and invulnerable to this spiritual misery. His work is an act of resistance. The sculptures Homme gothique, Main couchée (Reclining Hand, 1937), Homme cactus I and II (Cactus Man I and II, 1939-40) develop horizontal lines that spring out with evocative force. Before then, these lines were undulating, encoding hair. Here it is a threat and virility. Homme gothique is frontal and majestic. In Cactus II, the horizontal lines express positive/negative play. And the thorns are as dangerous as this war situation. His plastic vocabulary grew even larger. A new writing appears that I find in the blowtorch scarifications of my sculptures The Letter, 2000, and White Fire, 1999. González's oeuvre opened up new perspectives that were brutally interrupted. Tete à l'aureole (Head with Halo) was hanging on the wall in a very surprising corner. This work has often appeared in my Cerces (circles). It is the result of a typical process in González: discreet, private, almost secret. Such great intensity with such economy of means! Making a circle and a metal plaque enter a mystic dimension is almost a miracle. At a time of inflation of material means in making a work, González reminds us that he can create one of the most beautiful relics of the 20" century with very little metal!

The exhibition could also reflect the spirit of variety in González "as in life". He beats iron, bronze, silver. He carves stone. He is a master of direct attack. He incorporates elaborated elements, cast iron, found objects, which he welds together. His skill as an artisan always underlies his more daring investigations. A dialectic play is established between tradition and modernity. His work is linked to the long history of iron works and painting, which was his first vocation. Traditionally, the Louvre in Paris took in resident artists. They could create in contact with the great masters. Artistic life and history were maintained closely united. Today, the separation between old, modern and contemporary art is an unhealthy, sinister situation. It involves ignoring the profound nature of creation: an artist is contemporary with whatever he likes. Not necessarily with the living, whom he may consider to be sleepwalking or dead. Symbolic life is the only life that matters. The legal certificate of an existence is unimportant. I feel I am in direct contact with Carpeaux, Rodin and González. All the time.

For that reason, I particularly appreciate Kosme de Barañano's invitation to put my own selection of my works beside González's. The spiritual dimension of his work is rare in 20th century sculpture; Brancusi and Barnett Newman are among the exceptions that I find attractive.

I was intrigued by the friendship between Julio González and Edgar Varèse, whom I admire. It dates back to his stay in Burgundy. It marks common convictions that were affirmed throughout their existence. Their passion for religious architecture is one of the pillars of their creation: Tournus is a great reference in Varèse's musical universe. González frequented cathedrals. During that stay, he drew a portrait of Varèse's grandfather, who hung it in his New York home. He was very proud of it and often spoke of González with admiration. Varèse and Gonzalez searched for "interior rhythm". As Varèse lived in New York, I understand his insistence in saying "Oh, the Protestant mentality of those who ooze boredom and work as though they were doing their duty! The triumph of sensibility is not a tragedy." And he added, "Music is the embodiment of the intelligence that is in sounds".

Both artists are not in evanescence or sublimity but on a spiritual quest for the incarnate.

González's work transcends any formalist analysis so apt for the puritanical mentality. He has been too often "hygienized" by historians here in New York, reduced to a formal vocabulary.

In 1983 I wrote a text comparing his Catholic Catalan identity to that of the Protestant David Smith.

I would now like to draw attention to this excerpt from one of his last postcards to his family, written twelve days before he died:

“I recommend you go next Sunday to hear the Lenten sermon pronounced by R.P. Panice at Notre-Dame. It is very beautiful. Health and peace to you all, learn to live happily. I repeat, learn, you must learn and love. I never forget you. Love, Julio."

Today I repeat, learn to live happily, you must learn and love. Thank you, Julio González!

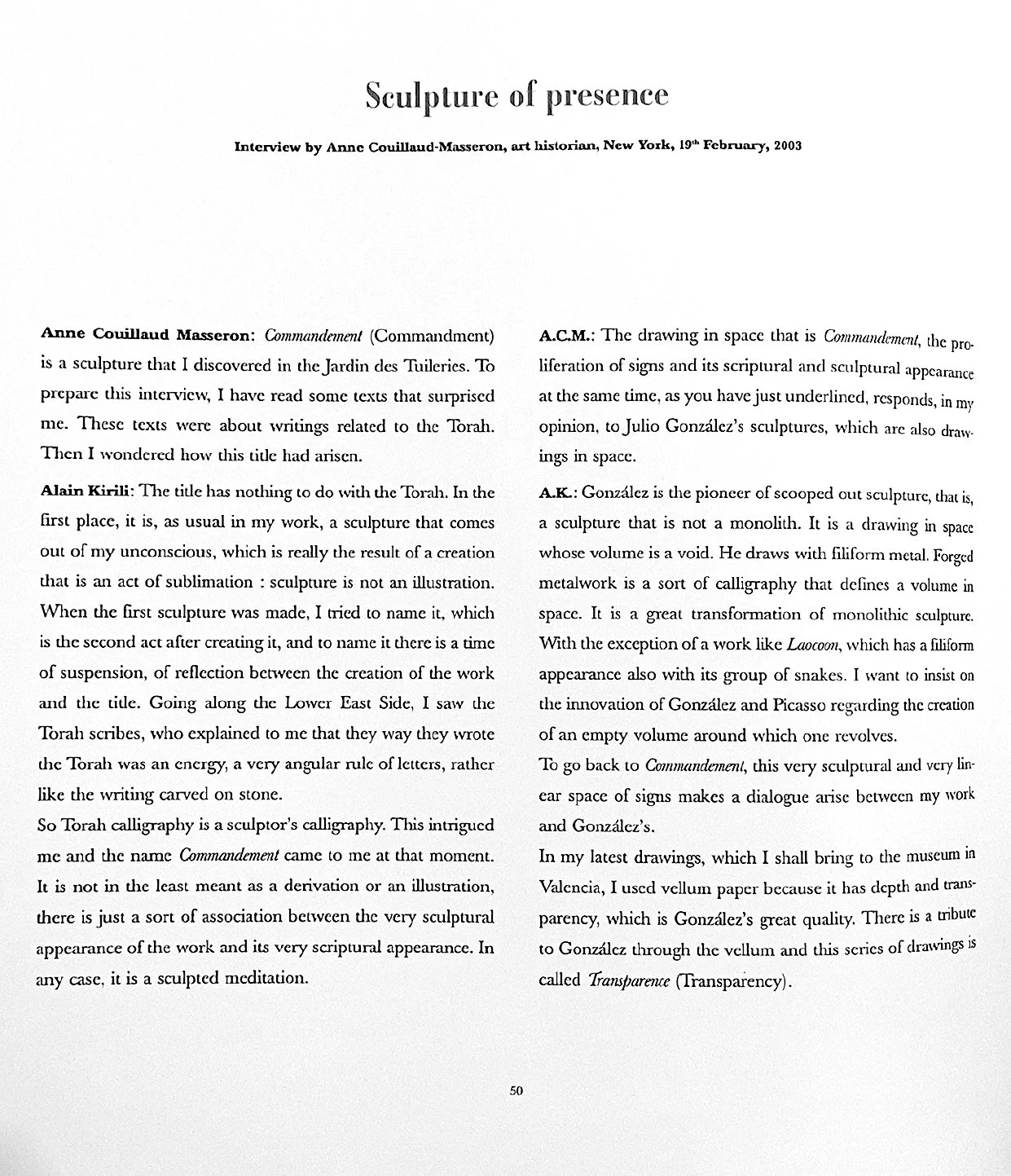

Alain Kirili, Belur III, 1984 (center)

Julio González, Le front 1934-6 (left) & Petit torse égyptien 1935-6 (right)

Alain Kirili, Méditation, 1990 (left)

Julio González, A la fontaine 1927-9, Nu à genoux de profil, 1929, Petit profil de paysanne, 1927-9 (right)

“I have situated these sculptures of González's obliquely, in interaction.

In this way, they catch the light and acquire depth.”

Alain Kirili

Some Remarks about my Selection of Julio González in the IVAM Collections by Alain Kirili, IVAM catalogue Homage to Julio González, 2003

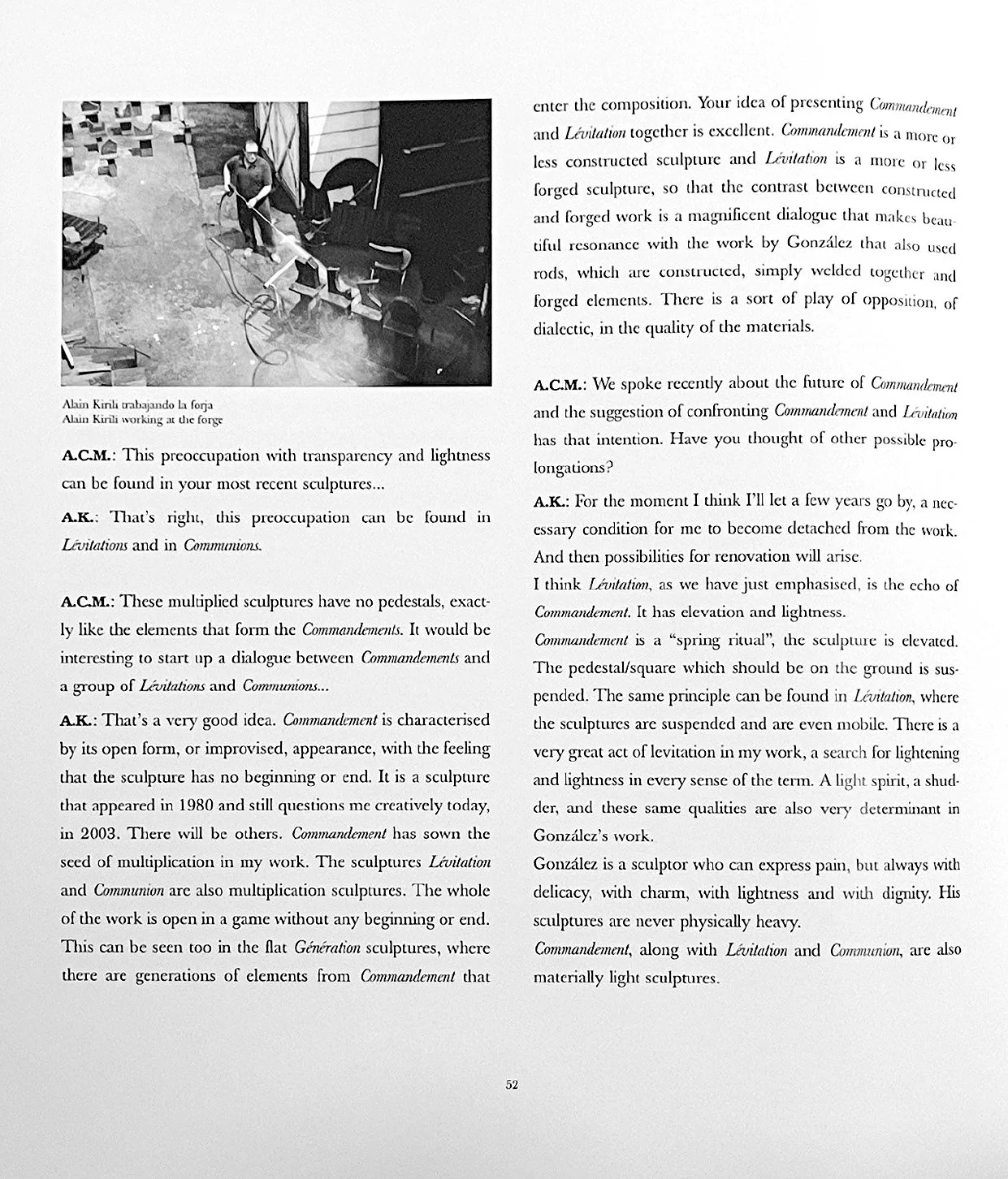

“ When going through my files recently, I was looking over my Crucifixion calligraphies. I learnt calligraphy in Paris when was about 18 and the Crucifixion had appeared unwittingly without any precise iconographic intention on my part. Christ, Golgotha, Calvary, the Passion, Levitation, the Resurrection... The same thing happened with my wrought iron crosses.

Forging, making calligraphic designs are activities deeply connected with writing, rapidly executed, while the unconscious can roam absolutely freely.

The blacksmith's trade, hammering, is never the result of an exploit or an effort. A piece of metal is beautifully forged when it has been well heated, red, yellow, incandescent. The metal is then enormously ductile and the hammer marks it quickly and with ease. Then the unconscious produces forms that become three dimensional questions.

In this way, all attempts at analogy are permitted. My assistant Anne could not stop comparing the cruciform appearance of the sculptures Communion (2002) and Lévitation (2002) with the drawings and crucifixes made twenty years earlier. The spiritual aura, the specifically Catholic iconography of González's work would favour this approximation.

The material lightness of all the works by González at the IVAM clearly reveals the close relationship between immateriality and spirituality in his work. The poetry in it stems from this economy of means. I would like to pay homage to him with my work, without any wish for comparison. A few modest approximations at the outside.

I have chosen works in iron for this exhibition because González is the poet of metal and I feel a very deep bond with his sharp sense of mysticism and Grace. It is above all a wonderful opportunity to exhibit in the González galleries: metal, stone, González is in any case the master of direct attack on materials. In this sense, thanks to the presence of my work the public will discover the great importance of Julio González aesthetic and ethic for the 20th century.

My most recent sculptures, Communion and Lévitation are forged elements suspended in space with columns that underline the reality of the void. The forged material reveals transparent spaces like the ones that exist in Julio González's maternities sculpted with metal rods.

After making these sculptures, I asked myself, as usual, what I had done. The transgressions are still mysterious, but the temptation to explain oneself persists. What has happened to me, why did I suddenly make these sculptures?

Then I looked for more or less formal similarities in history. I revisited the Hommage à Guillaume Apollinaire, a sculpture by Picasso dating from the early thirties, and I remembered the steel version enlarged in Picasso's lifetime, in 1972 (Museum of Modern Art in New York and that I had my photograph taken by Ariane Lopez-Huici in front of that monument in the company of Philippe Sollers.

Naturally, living in New York, I have seen Alberto Giacometti's Le Palais à quatre heures (The Palace at Four O'Clock, 1932-33) over and over again. it is a construction of extreme fragility made of wood and glass, wire and springs: an oniric construction.

I also think of David Smith's works from the same period Aerial Construction (1936) and Interior for Exterior (1939).

This little imaginary museum has in common with Julio González's oeuvre and, very modestly, with my own, an enormous wish to challenge weight, to challenge heaviness. The lightness in all these sculptures expresses in the best possible way poetic and spiritual refinement.”

from left to right (front pieces) : Alain Kirili, Alliance,1982, Summation,1981, Introït II, 1983, Citeaux II, 1982, Zahin, 1983

from left to right (back pieces) : Julio González, Petite Vénus, 1936-7, Tête plate dite “Le baiser” 1936 & Masque Marie-Thérèse inachevé, 1934,

Homme cactus dansant, 1939 & Main debout, 1937 , Les amoureux II 1932-3

“Since the time of David Smith most contemporary sculptors have not referred creation to religion ethics and sexuality together, as if, in a time of a commitment to plastic radicality, those references were anachronistic. By and large contemporary sculptors (of abstract as well as figurative work) have not been willing to brave Modern taboos and liberate major issues connected to their own identities. The commitment of Julio González to he Gothic art, for instance, is the source of a great difference between him and Smith. The mystical and graceful of González's sculpture emerged from his love for maternity, which derives from the cult of the Virgin and the art of the cathedrals. Smith, as a Calvinist, was in conflict with the Catholic Church and its representation of the female presence. Throughout Gothic art, sculpture reinforces its autonomy, plays with light and develops qualities of exceptional grace, through the cult of the Virgin. Statuary of the Virgin attained such a forceful spiritual expression of intensified muliebrity that in our time it has inspired sculptors as different as González and Lipchitz.”

Alain Kirili, Statuary vs Idols, 1986

Translated from the French by Jamey Gambrell

Installation of 3 drawings of Julio González (clockwise from top left) Maternité Mystique, 1940, Mère et enfant, 1941 , Petite tete cubiste, 1935, with the sculpture of Alain Kirili Berze, 1983 .