Alain & Ariane

Life & Art Together

Alain Kirili and Ariane Lopez-Huici shared a wonderful and rich life of art and love between Paris and New York and many more places. As a couple, they embody the beautiful and rare example of two artists living together, stimulating, supporting and respecting each other, creating side by side and sharing a common desire of love, art and humanity in its greatest diversity.

Discover below writings and memories from their unique history together.

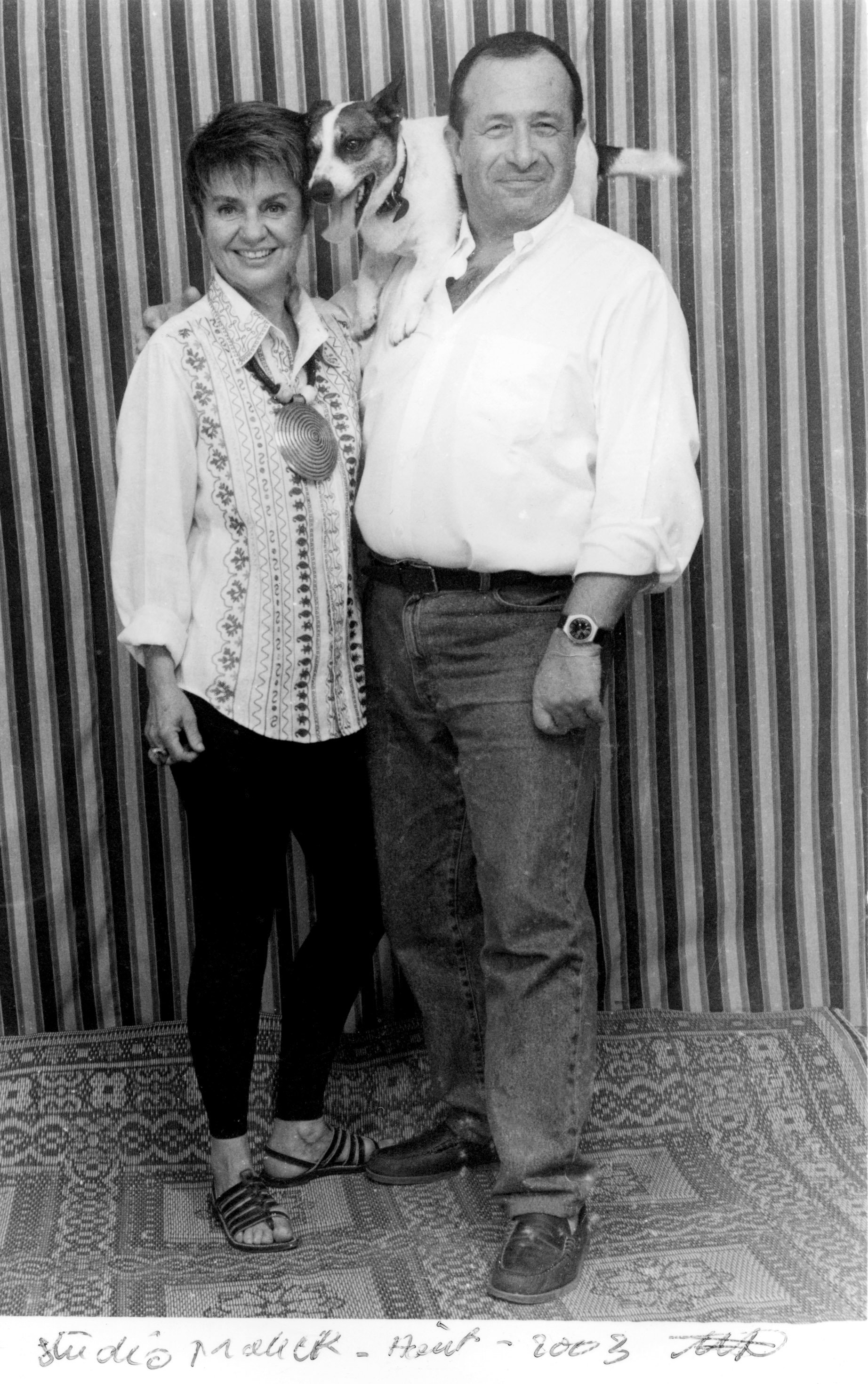

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Max and Alain Kirili, Août 2003

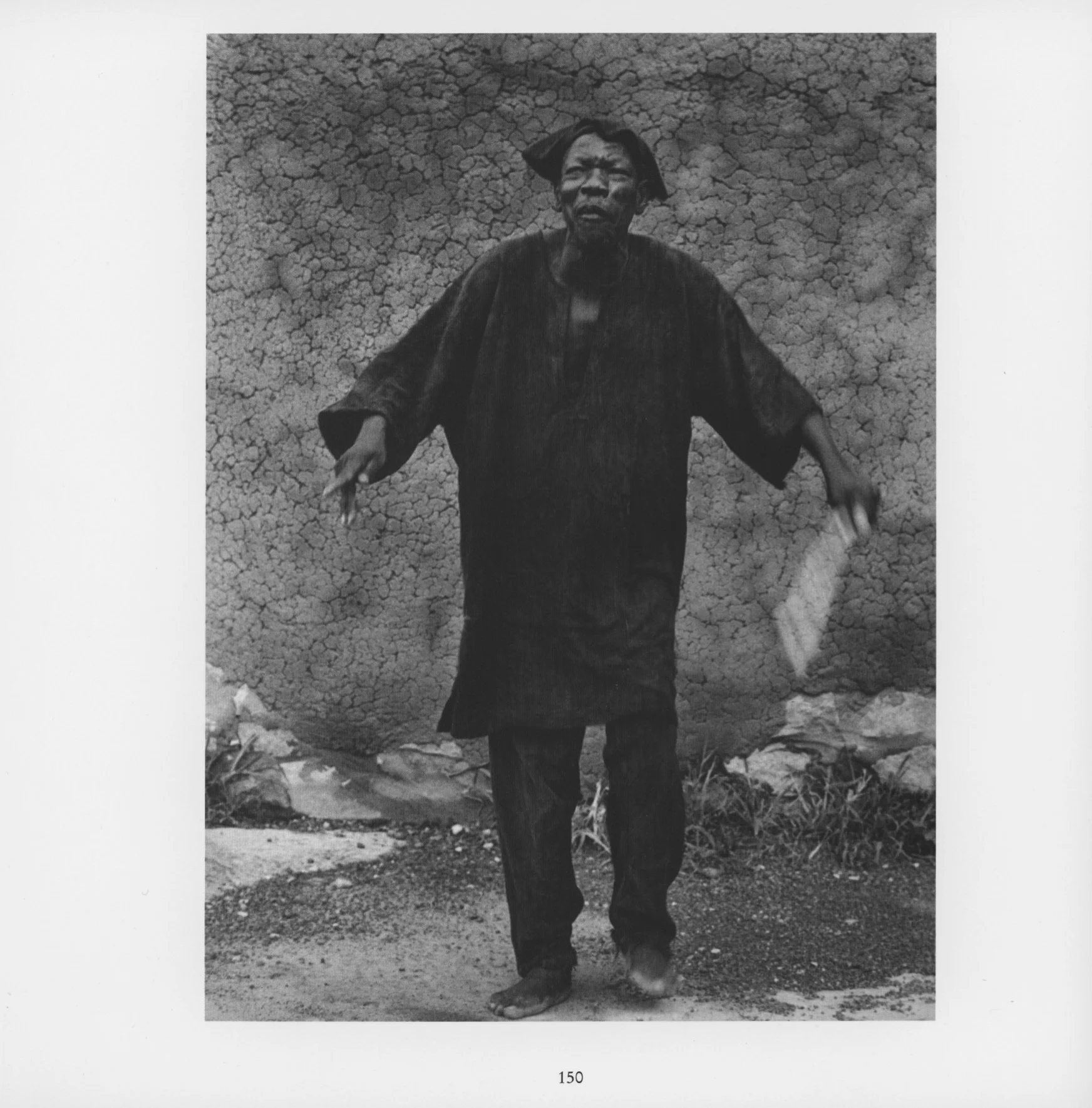

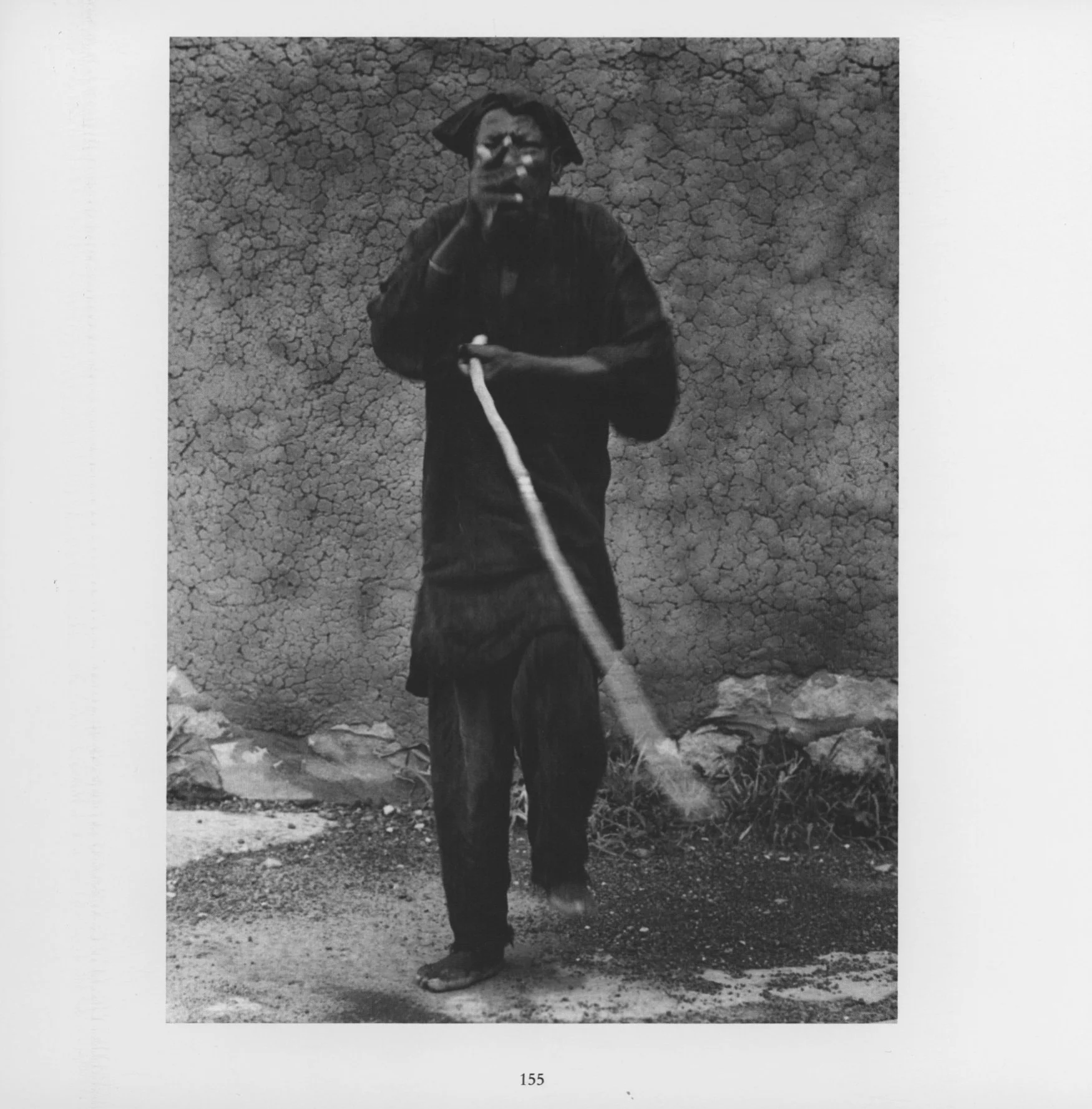

Photography by Malick Sidibé in his studio, Bamako, Mali

“ They’re a couple. He sculpts, she photographs. They are two; they live together, their works lie side by side, know each other, speak to each other – and love each other.”

Yannick Haennel

“Every marriage is an unwritten drama, a performance composed at once in conflict and complicity. Some are filled with dramatic incidents; in others, the passions run unobtrusively below the surface. The life partnership of Alain Kirili and Ariane Lopez-Huici is a production of more than thirty-five years’ duration—no longer a common thing in our era of shallow commitment. Inevitably, it has also been an artistic partnership, but not one in which it is easy for any third party to discern the specifics of the give- and-take of influence. Above all, they are not one of those “production-couples” that the philosopher Klaus Theweleit discussed in his book Object Choice (All You Need Is Love...), in which one partner becomes essentially the medium through which the other realizes his (usually his) artistic project. This marriage of true minds, rather, has been a duet of sovereign individuals whose projects have influenced each other by invisible gravitational forces.”

Barry Schwabsky

Ariane Lopez-Huici and Alain Kirili

White Street Studio, , New York, 2013

Photography by Marilia Destot

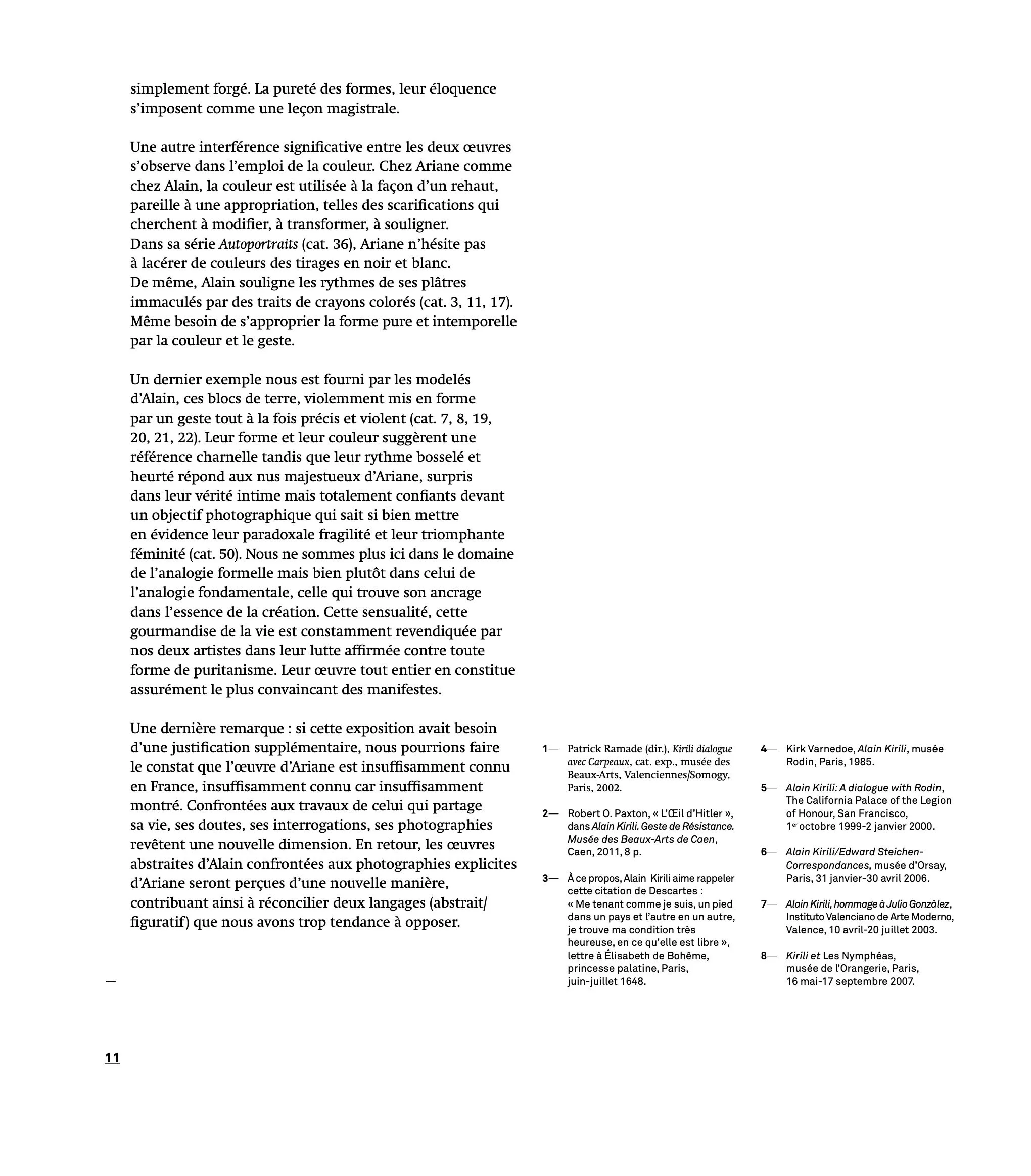

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Aviva, 1997

and Alain Kirili, King, 1986 and Zahin II, 1983

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

Photography by Laurent Lecat

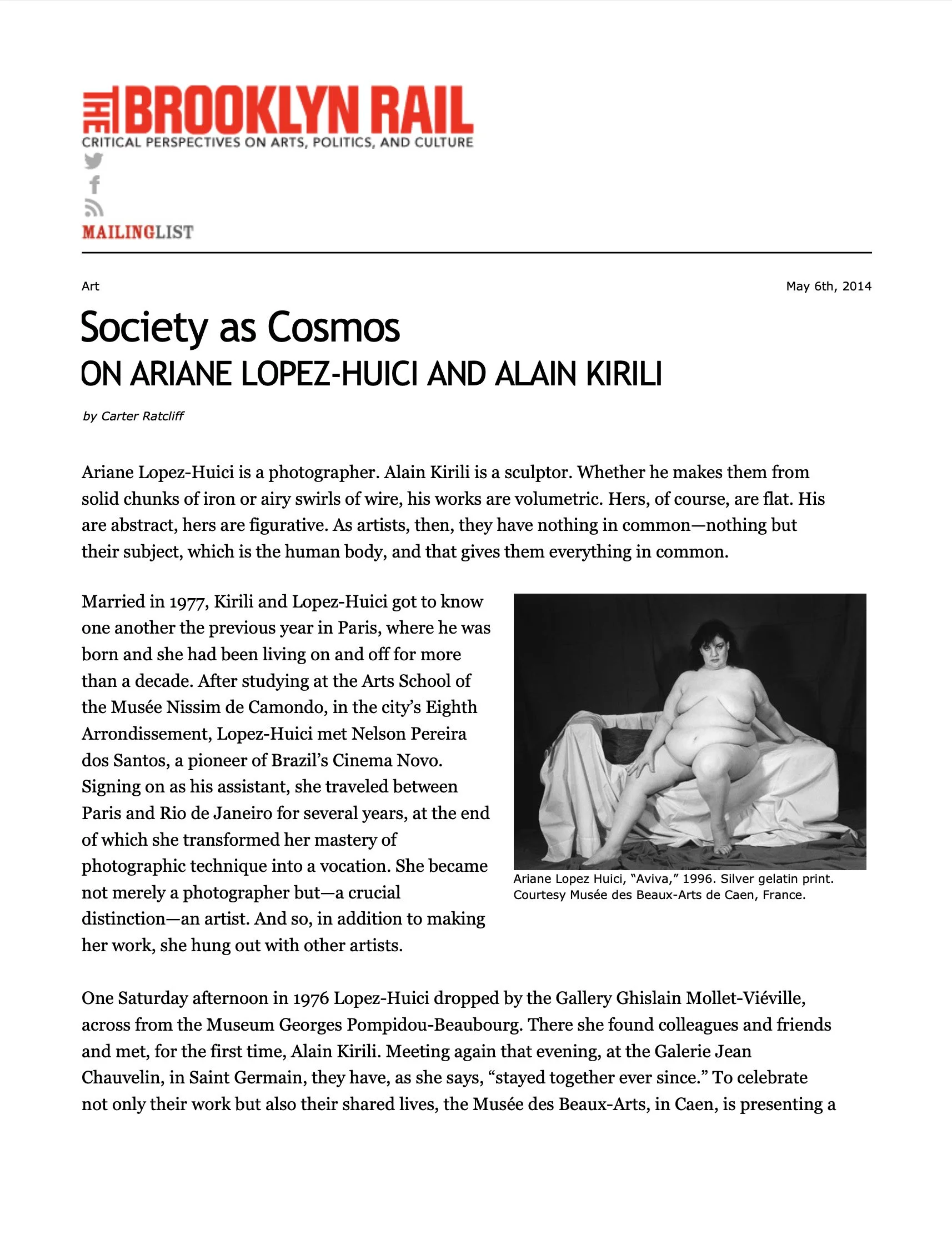

“Ariane Lopez-Huici is a photographer. Alain Kirili is a sculptor. Whether he makes them from solid chunks of iron or airy swirls of wire, his works are volumetric. Hers, of course, are flat. His are abstract, hers are figurative. As artists, then, they have nothing in common—nothing but their subject, which is the human body, and that gives them everything in common.”

Carter Ratcliff

“Une exposition qui propose une confrontation de l’œuvre de deux artistes, pour intéressante qu’elle soit, n’a rien d’exceptionnel. Mais si ces deux artistes forment

un couple dans la vie, comme dans la création, l’intérêt se double de curiosité car une telle présentation n’est finalement pas si fréquente. La littérature, l’histoire, mais aussi la presse se focalisent volontiers sur des relations fougueuses, des passions scandaleuses ou tragiques. L’histoire retient moins l’aventure calme et féconde de couples harmonieux qui se soucient de respecter l’autre, abandonnent le jeu des rivalités et des querelles, pour laisser s’épanouir des parcours résolument personnels. Alain Kirili et Ariane Lopez-Huici sont, assurément, exemplaires de cette dernière catégorie. L’un comme l’autre, ils ont choisi, tôt, de vouer leur vie à l’art et à la création.”

Patrick Ramade

Ariane Lopez-Huici and Alain Kirili

Exhibition Portraits Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

Photography by Laurent Lecat

ARIANE,

MESSAGERE DES DIEUX

by Alain Kirili, 1990

“J’ai eu beaucoup de chance de rencontrer Ariane en face de l’atelier du peintre Eugène Delacroix : il était un artiste de la passion. Après cette affirmation, je voudrais souligner que ma vie quotidienne et privée est une source essentielle de stimulation. Les titres de mes sculptures, comme Ariane, le signale !”

Alain Kirili

Extrait de La sonorité de la sculpture, un entretien avec Charlotta Kotik,

publié dans le catalogue de l’exposition Alain Kirili Sculptures à la galerie Marlborough Chelsea, New York, 1998.

Ariane Lopez-Huici,& Alain Kirili , New York , 2013

(photo©Marilia Destot)

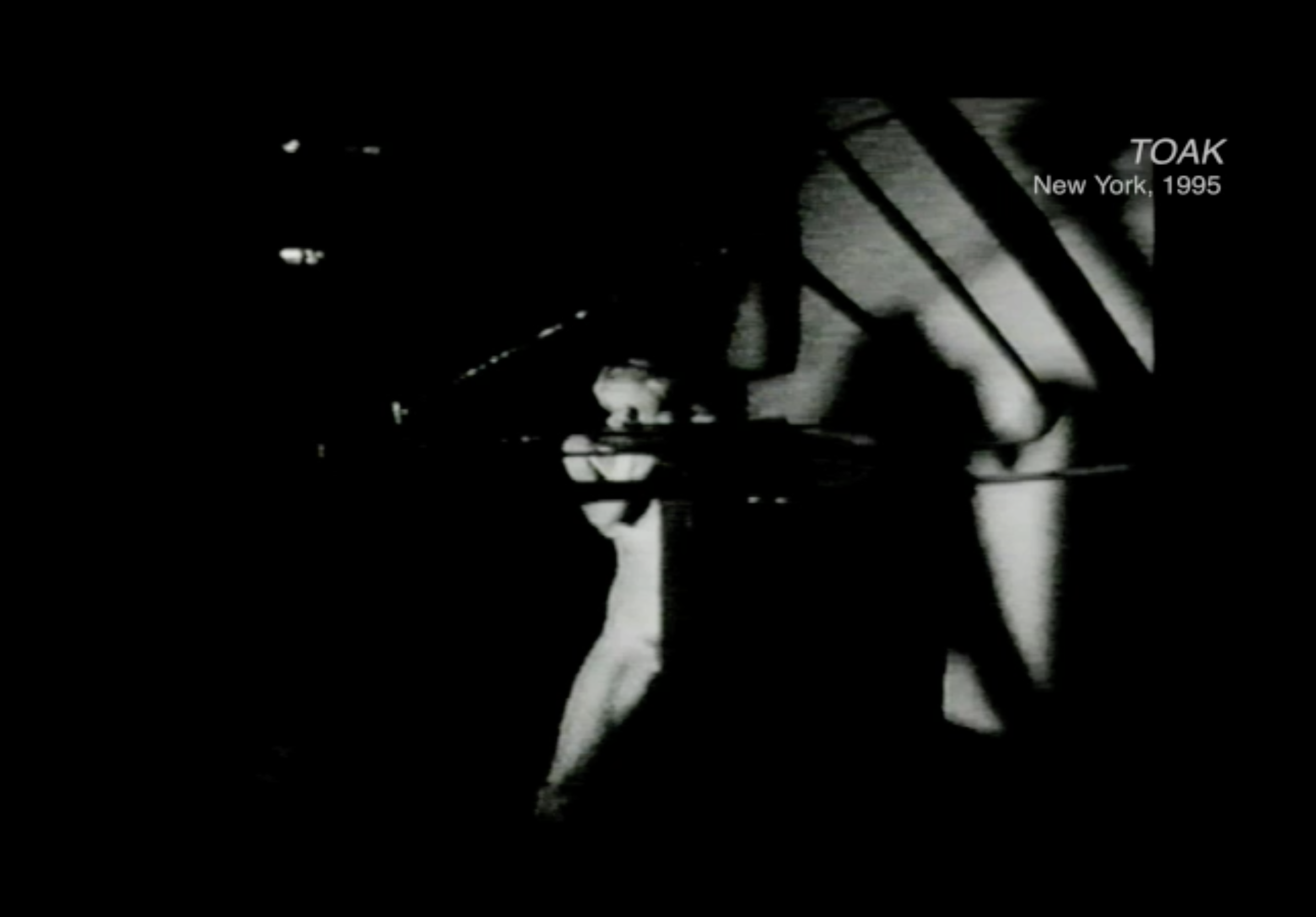

TOAK

by Ariane Lopez-Huici, 1995

a performance by Ariane Lopez-Huici in Alain Kirili’s sculpture Black Sound

filmed by Chrystel Egal with a music by William Parker

excerpt from the documentary Ariane Lopez-Huici, The Body Close-Up, by Marilia Destot, 2009

“To celebrate my 50th birthday, I decided to make a nude of myself. I asked my videographer friend Chrystel Egal to film me dancing in the nude.

The film answers two questions : First, would I have the courage to display myself in the nude at 50 years of age and thus defy time ?Second, would I be able to enter a trance, the way my models do, under the gaze of the other? Would I have the courage to run this risk? Again, this brings out the idea of a challenge, which is at the center of my artistic experience.

I was looking for a title that would be mysterious but also have a meaning for me. 10 years later, I can reveal that it means “To AK” and you can probably guess who AK is…”

“Pour fêter mes 50 ans, j’ai décidé de me mettre à nu moi-même. J’ai demandé à mon amie vidéaste, Chrystel Egal, de me filmer en train de danser nue.

Ce film répondait à deux questions : La première, aurai-je le courage de me montrer nue à 50 ans et ainsi défier le temps ? La seconde, serai-je capable d’expérimenter comme mes modèles la transe sous le regard de l’autre ? Prendre le risque de me mettre en danger ? Encore une fois, l’idée du défi au coeur de mon expérience artistique se révèle.

Je voulais un titre mystérieux , mais qui en même temps avait un sens pour moi. 10 ans après, je peux le dévoiler, Toak signifie en anglais To AK. Je vous laisse deviner ce que signifie AK…”

Ariane Lopez-Huici, 2009

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

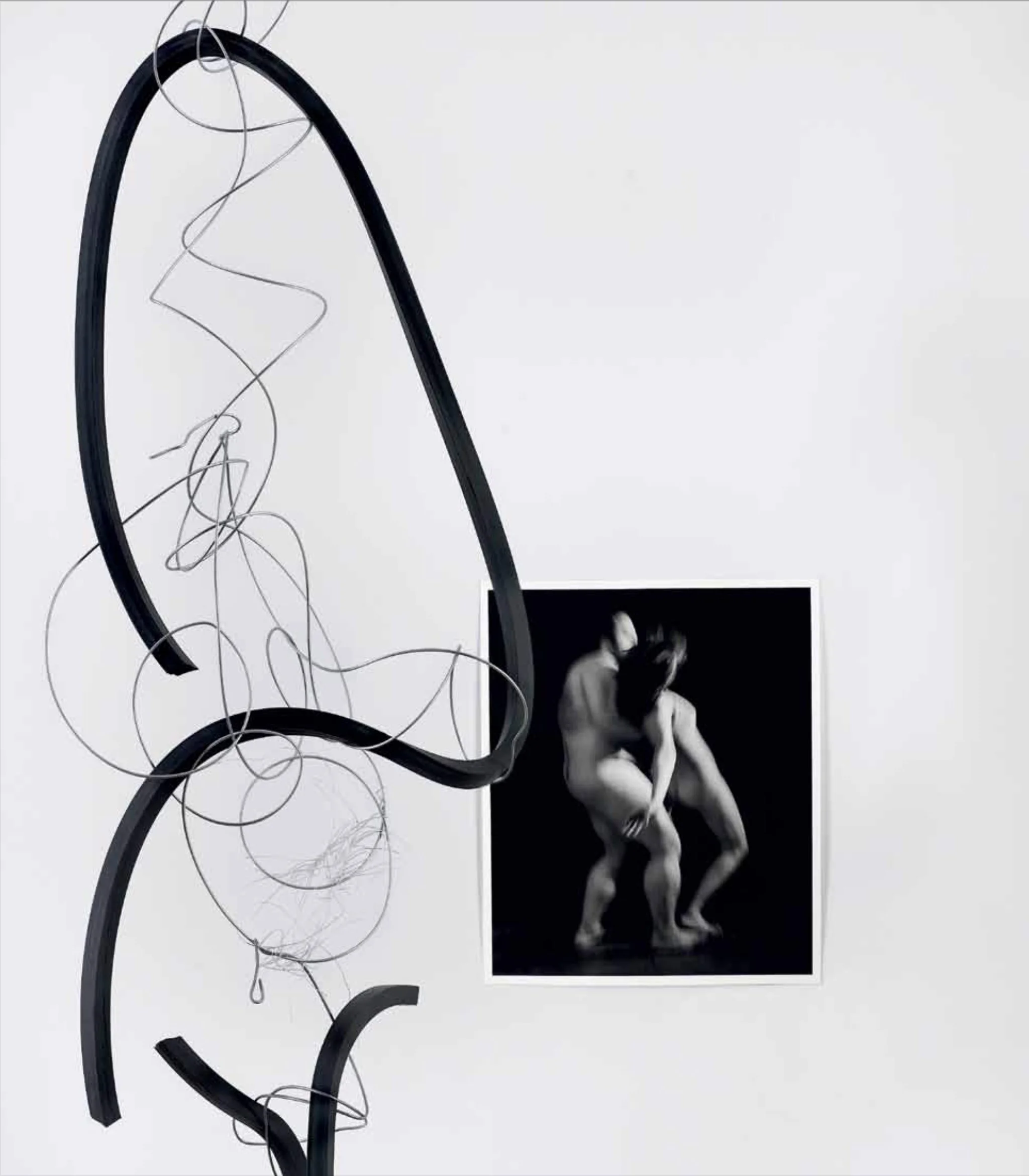

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Aviva, 1997, Alain Kirili, Commandement XV, 1991

( photos © Laurent Lecat )

Parcours croisés

par Patrick Ramade

Introduction à l’exposition, publiée dans le Catalogue Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

left : Ariane Lopez-Huici, Shani Ha, 2013, Alain Kirili, Adamah, 2011

right : Alain Kirili, Aria , 2012, Ariane Lopez-Huici, Holly &Valeria, 1998

( photos © Laurent Lecat )

PARCOURS CROISÉS

Entretien entre Alain Kirili et Ariane Lopez-Huici

New York, janvier 2013

publié dans le Catalogue Parcours croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

Alain Kirili

Je me suis toujours intéressé aux dialogues entre les artistes, contemporains ou non. Par exemple, en 2001, à New York, la galerie Pace a organisé un dialogue entre un peintre et un sculpteur : De Kooning et Chamberlain. Nous sommes quant à nous deux artistes, une photographe et un sculpteur, qui creusons le sillon de nos œuvres indépendamment des tendances et des effets de mode. Pour cela, il faut une certaine détermination et la capacité à assumer le fait de se tenir en quelque sorte éloigné de l’actualité. Cette confrontation à l’intemporel, qu’en penses-tu ?

Ariane Lopez-Huici

Je me souviens très bien de cette exposition car j’ai été très intriguée par le caractère osé de cette confrontation. Deux artistes d’âge différent, De Kooning (1904-1997) et Chamberlain (1927-2011) ; qui plus est, formellement différents : peintre et sculpteur ; d’origines différentes : De Kooning né en Hollande, Chamberlain à Rochester, aux États-Unis.

Mais l’exposition était formidable, car au lieu de juxtaposer les œuvres de façon académique, elle laissait au contraire l’imagination libre. C’est ce que j’espère réussir en répondant à l’invitation de Patrick Ramade.

Je voudrais également dire combien l’œuvre de De Kooning se réverbère dans mon travail car il a mené de front en même temps les fameuses Women et un travail abstrait. Voilà qui est bien insolent ! Pour revenir à ta question quant à notre indépendance vis-à-vis des tendances actuelles, je dirais que oui, on peut se sentir isolé par rapport au marché de l’art mais certainement pas par rapport à l’Art car les personnes qui aiment mon travail et le collectionnent sont elles aussi d’irréductibles indépendants. Alors, vive la différence !

A.K.

Tes photos sont pour moi une grande source de stimulation car elles cherchent la vérité du nu.

Tes nus ne camouflent pas la nudité mais la révèlent. Chaque génération exprime l’état de la civilisation et de la morale à travers la représentation du nu. Ainsi, il y a des nus frigides, des nus qui cachent l’audace de la nudité. J’ai titré des sculptures de modelés en terre cuite Nudité : l’abstraction du modelé exprime le rythme secret de mes pulsions et révèle mon inconscient pour insister sur la vérité impudique de ma sculpture. Révéler son inconscient est un défi lancé à la pudeur, à la rétention. Créer, c’est oser et c’est là le sens profond du terme « nudité » que j’oppose à celui de « nu ». Je ressens, grâce à tes photos, la singularité et le courage de tes modèles qui, de ce qui pourrait être des handicaps, font des atouts pour se dépasser. En se déshabillant, ces modèles atteignent même un niveau de vérité héroïque qui se transmet dans mon œuvre. Rien n’est déprimé, tout est tendu vers l’élévation. Ce dépassement n’est possible que par la relation, me semble-t-il, que tu crées avec tes modèles.

J’admire les émotions qui se dégagent et qui prennent de l’ampleur du fait que tes modèles sont très singuliers, avec des personnalités telles que celles de Dalila Khatir, Anne Sillinger et Priscille Vincens. Je constate que c’est dans la singularité que l’on atteint une vérité universelle, et dans la confiance que des émotions peuvent s’exprimer Révéler son inconscient est bien un défi lancé à la pudeur, à la rétention. La caresse est un acte sensuel qui peut rester en surface et permet d’échapper à celui qui consiste à attaquer directement la terre, le fer, qui sont pour moi les métaphores de la chair. Tes photos me semblent relever du même genre d’attaque ; elles sont faites très vite, sans volonté de perfection, et gardent le grain propre au développement argentique. L’art sensuel manque de sexualité. Il devient vite lisse, glacial, en atteignant une perfection distante objectivée. L’imperfection est pour l’art essentielle car elle est le signe de l’humanité.

A.L.-H.

Il est toujours difficile de dire les pourquoi et les comment des choses, mais quand j’ai abordé ce beau sujet du corps je me suis sentie attirée par des corps différents dans lesquels je devinais une certaine blessure qui ajoutait au mystère de la vie. Il n’y a pas de beauté sans mystère. Photographier me permet de montrer non seulement ce que je vois mais surtout ce qui se cache. Les corps, dans tous les excès, de la chair, de la passion, voilà ce qui m’intrigue : l’exubérance comme forme de beauté. Toute beauté est singulière. Aviva, Dalila, Anne, Priscille sont devenues des amies et cette confiance qui s’est établie entre nous a permis d’aller plus loin encore dans cette mise à nu du corps. Cette fresque du corps, nous la concevons également dans le temps, avec toutes les surprises que réserve la vie. À mon tour de te poser une question : depuis de nombreuses années, nous organisons dans notre atelier à New York des concerts de free-jazz et cela me fait penser à une remarque qu’a faite Odile Vivier dans son livre sur Varèse : « Il vénérait Satie et particulièrement le Kyrie de la “Messe des pauvres”, cette musique qui tourne sur elle-même comme une sculpture. » Peux-tu développer cette relation entre musique et sculpture dans ton travail ?

A.K.

Il existe un rapport entre l’émergence de l’abstraction et la musique moderne. Il suffit de reprendre les dialogues entre Kandinsky et Schoenberg. La notion d’improvisation chez Kandinsky et celle du free-jazz appartiennent à la même lignée. Le mot « improvisation » est devenu un titre pour les peintures de Kandinsky et pour un album d’Ornette Coleman (The Art of the Improvisers, 1959).

Quand et pourquoi passes-tu du figuratif à l’abstraction ?

A.L.-H.

J’ai toujours fait en même temps des photos abstraites et des photos figuratives. Je ne vois pas de différence, car en réalité j’essaie d’exprimer des émotions.

C’est probablement un mot très osé de nos jours, mais je l’assume. On pourra peut-être méditer sur la frigidité des nus de Bougereau et sur les vibrations brûlantes des abstractions dans les Boogie Woogie de Piet Mondrian. Qu’elle soit abstraite ou figurative, une œuvre d’art doit exprimer un certain émoi érotique.

Mais je voudrais revenir sur le sujet de cette exposition, la confrontation de deux artistes qui sont en même temps unis dans la vie. Je dirais que, fondamentalement, il faut être stimulé, encouragé et défendu dans la voie difficile qu’est la création. Et qu’il faut laisser à chacun un champ de liberté. Le fait que chacune de nos œuvres corresponde, tout en relevant de deux pratiques différentes (sculpture et photographie), montre bien que nous faisons les mêmes rêves.

A.K.

Une exposition à deux, évidemment, c’est bien plus qu’un dialogue : elle met en jeu le dit et le non-dit, le respect de l’espace de liberté de chacun dans la vie d’un couple. Aragon se risqua à une confidence en disant au sujet d’Elsa Triolet, en 1968, « Quarante ans de nous deux »...

Le sculpteur Gaston Lachaise, avec lequel j’ai fait dialoguer mes œuvres à New York en 2007, frôlait souvent le grotesque. Il me semble que cet élément n’existe pas dans ton œuvre. Pour exprimer la puissance de tes modèles, tu ne forces pas le trait. Tes modèles s’affirment d’eux-mêmes avec toute la dignité que tu aimes tant saisir.

Le sujet de tes photos tourne autour de ce que Georges Bataille appelait des « visions d’excès » : découvrir l’élégance à travers une beauté organique et convulsive, vivante et charnelle, voilà la vie qui émerge. Je ressens cette éthique dans le dialogue de tes photos avec mes terres cuites modelées, mes fils de fer, et mes pièces forgées. Je dirais même que tes photos sont aussi tactiles que mes sculptures. Qu’en penses-tu ?

A.L.-H.

Photographier le corps humain, modeler la terre cuite, forger le fer, créer, en somme, exige un optimisme irréductible face à un monde qui n’est somme toute qu’humain. C’est pour cela que je dirais avec Spinoza : « La seule perfection, c’est la joie. »

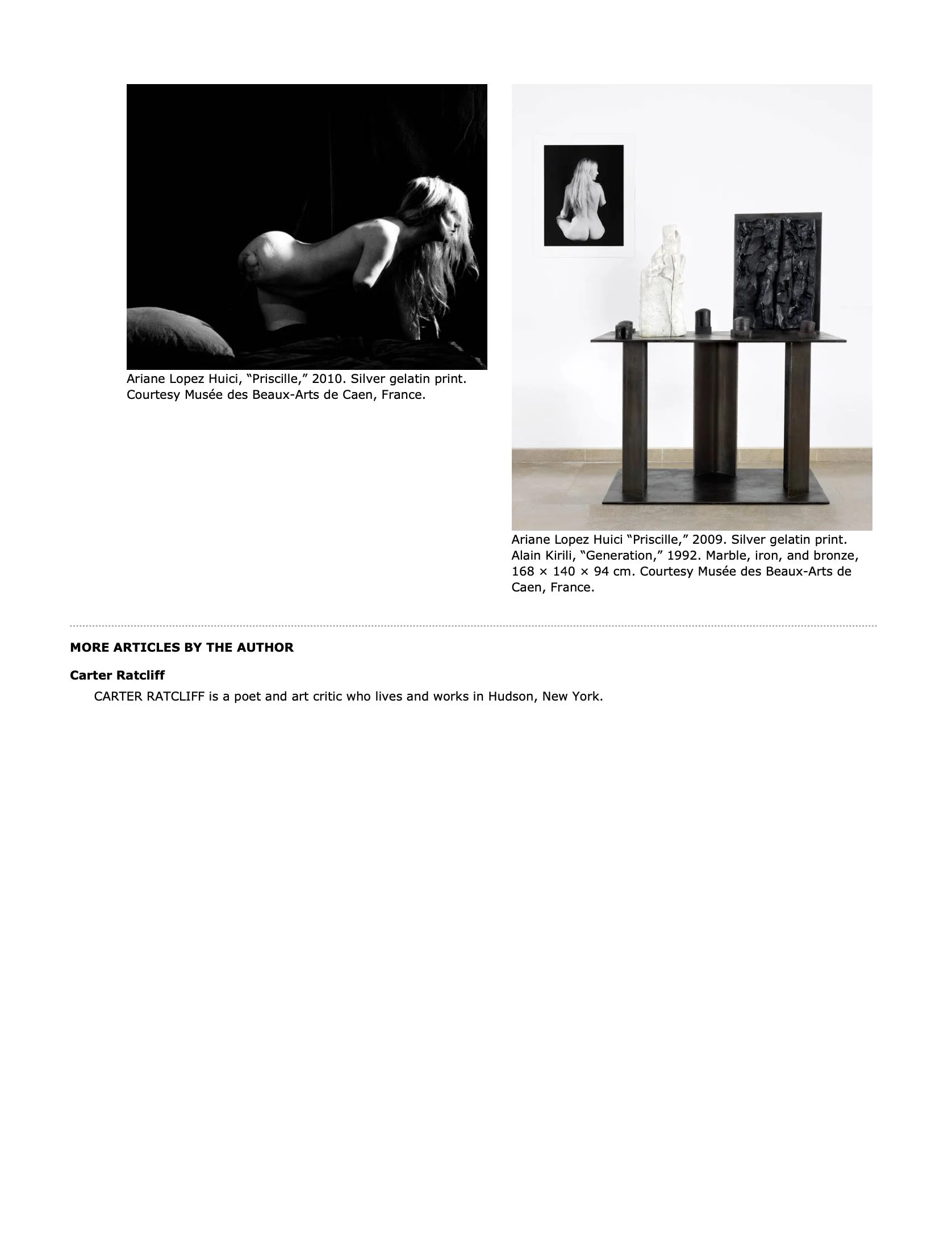

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

left : Ariane Lopez-Huici, Les Lutteurs, 2003, Alain Kirili, Zahin II, 1983 and Meditation, 1983

right : Ariane Lopez-Huici, Priscille, 2009, Alain Kirili, Generation,1992

( photos © Laurent Lecat )

Duo Absolu

by Barry Schwabsky

published in the exhibition catalogue Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

Every marriage is an unwritten drama, a performance composed at once in conflict and complicity. Some are filled with dramatic incidents; in others, the passions run unobtrusively below the surface. The life partnership of Alain Kirili and Ariane Lopez-Huici is a production of more than thirty-five years’ duration—no longer a common thing in our era of shallow commitment. Inevitably, it has also been an artistic partnership, but not one in which it is easy for any third party to discern the specifics of the give- and-take of influence. Above all, they are not one of those “production-couples” that the philosopher Klaus Theweleit discussed in his book Object Choice (All You Need Is Love...), in which one partner becomes essentially the medium through which the other realizes his (usually his) artistic project. This marriage of true minds, rather, has been a duet of sovereign individuals whose projects have influenced each other by invisible gravitational forces.

For both Kirili and Lopez-Huici, a deep sense of the integrity of one’s project does not conflict with but is in fact integral to the realization that this project flourishes through the encounter with those of others and not through some protective isolation. “I have never avoided the influence of others,” Henri Matisse told Guillaume Apollinaire. “I would have considered this cowardice and a lack of sincerity toward myself. I believe that the personality of the artist develops and asserts itself through the struggles it has to go through when pitted against other personalities.”(1)

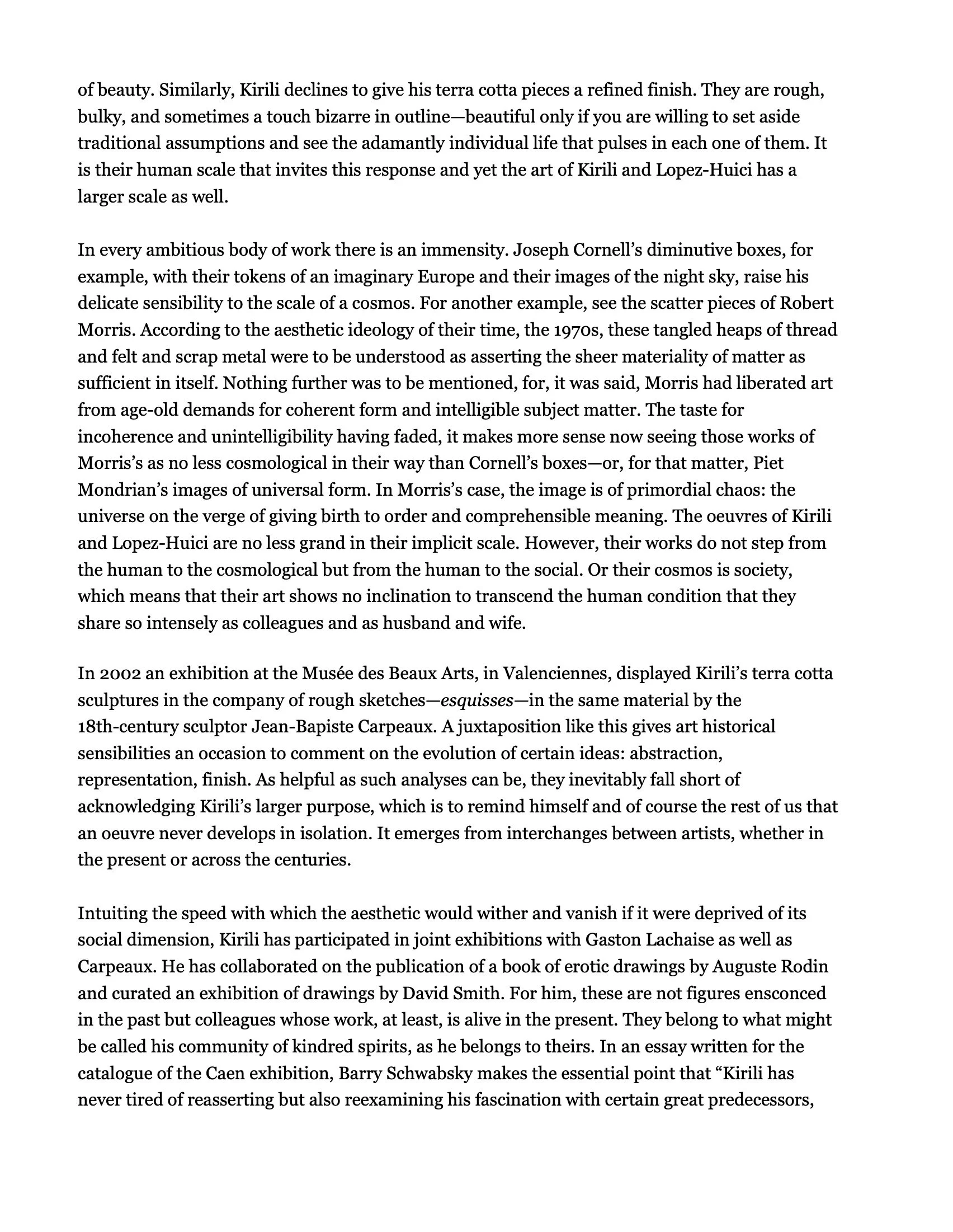

Kirili in particular has been clear in his loyalty to this Matissean ethics of influence. He has never tired of reasserting but also reexamining his fascination with the work of certain great precursors, above all David Smith and Auguste Rodin as well as the anonymous creators of ancient Indian yoni-lingam sculptures. Nor has he hesitated to exhibit his works alongside those of Julio González, Gaston Lachaise, or Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, or to invite such musical masters as Cecil Taylor, Steve Lacy, or Billy Bang to embroider their improvisations around their perceptions of his forms. And what is true at an individual level is also true at a broader cultural level; not only in his love for Indian sculptural forms and their attendant ceremonies but also in his collaborations with American and African artisans, he is (as Robert O. Paxton has put it) “engaged in free artistic exchange with other peoples without losing his own identity.”(2)

As for Lopez-Huici, although her approach to photography has certainly never been such as to occlude her affection for her Pictorialist and modernist precursors, especially those whose studio practice emphasized a constructed, performative dimension. But her work’s openness to others has come most patently through her interactions with her subjects—who are much more than subjects in the usual sense. Although her early works were abstract, since the early 1990s her images has developed out of very close collaborations with a fairly restricted number of models with whom she works on an intensive and long- term basis, among them Daniel D., Aviva, Bill Shannon, Dalila Khatir, Priscille... a wonderfully diverse group of people who in realizing and revealing before the camera their own aesthetics and ethics of the body have allowed Lopez-Huici, in parallel, to articulate her own.

The aesthetics and ethics of the body—here is the terrain, above all, where the otherwise so different oeuvres of Lopez-Huici and Kirili find their common ground. But each one populates this territory in a distinct way. Some of the differences, of course, emerge almost naturally from the differences between sculpture and photography as material entities. A three-dimensional sculpture is already in itself a kind of body, occurring in real space. By contrast, a photograph is a flat sheet of paper with no ostensible figural being of its own; if it concerns the body, it can only be through an appeal to the imagination—but this is not to say that it must be imaginary. Rather, it always appeals an empirical presence (albeit one that is fixed in the past by the time the photograph has actually been printed). As Roland Barthes put it, the photograph “always leads the corpus I need back to the body I see.... The photograph is never anything but an antiphon of ‘Look,’ ‘See,’ ‘Here it is’; it points a finger at a certain vis-à-vis, and cannot escape this pure deictic language.”(3)

The photograph of a certain body is always, indeed, of that body. And it is not just that the photograph points at this body, but also that, in a certain sense, that body was also pointed toward the camera, and toward the eye of the photographer who framed it in her viewfinder before the resulting picture was ever framed on a rectangular sheet of paper; certain rays of light reflected from that body through the camera’s lens and onto the negative.

Undoubtedly this distinction between a real (but inanimate) body in sculpture and an imagined one (but empirically existent and living at the time of the shutter release) in the photograph is too simple. There are other nuances to consider. As Kirili well knows, for instance, the viewer’s relation to the body of the sculpture may be inflected by a sense of the maker’s body in action as the object was worked in time as it was created. In this sense the sculpture unexpectedly shares something of photography’s reference back to a certain past moment; sculpture too has a “deictic” aspect. But by the same token, in Lopez-Huici’s photography—as the late Jeanne Siegel wrote as long ago as 1990—“photography... identifies with a sculptural attribute,” seeking to communicate a sense of three-dimensionality and of explicitly tactile sensations.(4)

In her photographs of that time, Lopez-Huici often took sculpture as a source for her imagery. Over the last couple of decades, on the other hand, with her art centered on the collaboration with her models, it would not be inaccurate to say that she conceives of these models as living sculpture. This is her special sense of the body: That it is not primarily a material thing that is separate from the self. Rather, it is the creation and expression of the person. “The body is not a thing,” as Simone de Beauvoir emphatically put it. “It is our grasp on the world and the sketch of our project.”(5)

Beauvoir’s idea of the body as a sketch means: It is a work, but it is an (always) unfinished work. The same notion is present in the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who could easily have been explicating Lopez-Huici’s photography when he wrote that, “Whether it is a question of the other person’s body or my own, I have no other means of knowing the human body than by living it, that is, by taking up for myself the drama that moves through it and by merging with it. Thus, I am my body... and reciprocally my body is... a provisional sketch of my total being.”(6)

This idea of the body as a sketch is present throughout Kirili’s work as well. Marks of the gestures of modeling, of forging, and the like—the sculptor’s “grasp on the world,” to borrow Beauvoir’s words—are, in the tradition of the great modernist manifestations of the unfinished as a positive value from Manet onward, traces of the process of making, reminders that the work is essentially oriented toward the ongoing present and not something sealed off in the past. But each of those marks is also the index of a moment, like the trace a certain light leaves on a photographic negative. The object is a kind of body, but also the sketch of a possible body. The sculptor takes up the drama that moves through it, as Merleau-Ponty says; in a different way the viewer must do so as well. The point is that art exists in what is often called its medium—in iron, in plaster, or (as in some astonishing recent works by Kirili) in wire and rubber; in photographic emulsion on paper; in a living body in movement, no matter—only insofar as it participates in this drama, an encounter that shakes it, that puts an end to its stasis, that transforms it. Lopez-Huici has said it beautifully: “Whatever medium you use—painting, sculpture, photography, etc.— what is at stake is always the establishment of that very intense grappling, body to body, with what I would call the great themes of life.”(7) It is a great and solemn yet joyous performance, here over many years marvelously accomplished à deux.

(1) Henri Matisse, Matisse on Art, revised edition, ed. by Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), p. 29. Original in Écrits et propos sur l’art, ed. by Dominique Fourcade (Paris: Hermann, 1972), p. 56.

(2) Robert O. Paxton, “The Eye of Hitler,” http://www.kirili.com/textesE/2011_09_Paxton_English_Caen_version.pdf.

(3) Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, tr. by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), pp. 3-4. Original in La Chambre claire in Oeuvres completes V: 1977-1980, ed. by Éric Marty (Paris: Seuil, 2002), p. 792.

(4) Jeanne Siegel, “Erotic/Fragment: Ariane Lopez-Huici’s Tactile Photographs,” Arts Magazine, November 1990, p. 99.

(5) Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, tr. by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (New York: Vintage Books, 2011), p. 46 (translation modified).

(6) Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, tr. by Donald A. Landes (New York: Routledge, 2012), p. 205. Original in Phénoménologie de la perception in Oeuvres, ed. by Claude Lefort (Paris: Quarto Gallimard, 2010), p. 887.

7) “The exemplarity of the model: Conversation between Ariane Lopez-Huici and Paul Audi,” in Ariane Lopez-Huici (Valencia: IVAM, 2004), p. 42.

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

left : Ariane Lopez-Huici, Les Rebelles, 2006, Alain Kirili, Meditation, 1983

right =: Ariane Lopez-Huici, Holly&Valeria, 1998, Alain Kirili, sans titre, fil de fer suspendu, 2014

( photos © Laurent Lecat )

Surgissement à deux

par Yannick Haenel

publié dans le catalogue d’exposition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

RISING

by Yannick Haenel

translated by Philip Barnard, published in the exhibition catalogue Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

They’re a couple. He sculpts, she photographs. They are two; they live together, their works lie side by side, know each other, speak to each other – and love each other.

Most artists are alone; their solitude haunts their oeuvre and sometimes pulls it downward into storied misery. Here, quite rarely (by contrast I think of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner), there are two: their solitude is doubled. Moreover: this doubled solitude makes their two oeuvres larger, it multiplies their logics of unforeseeable encounters, it circulates the desire that enhances them, it makes possible what the world’s simultaneous globalization and disappearance into the virtuality of networks is making increasingly impossible: the mad simplicity of a relationship—what I call love.

Juxtapose this totem in forged black iron by Alain Kirili and these strange oculi photographed by Ariane Lopez-Huici; conjugate this celestial sphere mysteriously looming out of the ashen folds of the universe with these rubbery strings forming silhouettes in weightlessness: what happens between them? What happens in you? Their play on visibility is infinite: an invisible bacchanalia, a silent conversation, overflowing volumes, strangeness sung. Here space meets you or, simply, here space loves you.

In a sculpture by Alain Kirili, in a photograph by Ariane Lopez-Huici, what immediately becomes evident is: someone is there.

This someone is not alone, in the sense of unhappy subjectivity: this someone is a volume of thought that desires—it thinks of the other, of all the others who are not itself; and this thought, which is in every sculpture and every photograph, makes the world open itself with love: blocks erected, slits willed, grooves, twists, embraces, wrestling, masturbations, abductions, nudities, drunkenness.

When I see a sculpture by Alain Kirili, I glimpse divinity. As it is put in Homer: “he saw the god.” Yes, in Kirili, the hammer at the forge rumbles with the laughter of a calm god.

And when I look at photographs by Ariane Lopez-Huici, I realize that this god is Eros, the same one Parmenides tells us was born before all the other gods: Eros who emerges directly from Chaos, and who in some traditions is likened to a demon—a troubling, tumultuous force that inhabits, for example, the exuberant body of Dalila, as she intensifies the motions of a plump sibyl, with her primordial hilarity and overwhelming flesh.

The word “love” erupts immediately when I think of this couple of artists. Nothing in it blares out, nothing in it is saccharine: Eros is a god who knows that which is terrible.

The oeuvres of Ariane Lopez-Huici and Alain Kirili thus possess a threatening truth, a troubling knowledge that seems to come from darkness, even though neither ever indulges in the cynical teeth-grating that inhabits contemporary art like a poison: their power is propitious, their timbre is liberated—their works spread out in the affirmative tracing of joy, delighted like a couple making love.

Look at these painted forged iron pieces by Alain Kirili, these blocks of universe, these declamatory stones, these assemblages that, in their laughter, bid farewell to petty enclosure, these painted plasters throwing off red flames that speak sexual churning, these iron wires twisted upon themselves like storms of desire, these dancing rubber strands.

Look at these bodies photographed by Ariane Lopez-Huici: bodies that hold each other tight, that struggle, that exult; bodies that tear themselves away from the metrics, programming, and norms of fashion images; bodies with insolent tranquility, fleshy and rebellious, in crude postures, with disturbing joys; bodies that aren’t afraid of their suffering, their fat, their aging; bodies that can know themselves, that project their excess just as easily as their lack, that don’t keep themselves from existing; bodies that affirm time and their final destinies, and the courage to live in nudity in a living present.

“Artists are initiates,” Alain Kirili says often. They have access to another country—one that gives you knowledge about death. There is a path that leads through the heart of hell, but is protected from damnation. On this path artists make their way: they pass through, like Job, so they can tell you—and so that they can invite you too to witness this unharmed, or, in other words, to reinvent pleasure.

Here we enter a high, airy space, where the air itself opens up, transpierced by metal. Alain Kirili’s forge work creates shadows, and all of its darkness brings light to a colorless world.

Violence of voluptuousness, black throat, arms spread wide, a grasping sex: the black depths of Ariane Lopez-Huici’s photographs, sounding chasms, eyes from caves. The bodies erupt from an original wall that is the hole of the species.

In both artists, there is a fundamental affirmation of guiltlessness, or in other words, of that which is not absorbed by hell—that which resists it.

Hell (planetary society) attacks us every day; it seeks nothing else: to reach us, to sap our strength so that we end up joining forces with what destroys us, with destruction itself.

An artist—and here there are two—is someone who doesn’t get fooled by the devil; who never ceases, who has the endurance and the cunning, to outplay the nihilist strategy—to escape capture.

Whence these exuberant exorcisms: these couples in Ariane Lopez-Huici who grapple, clutch, and knead one another; these iron wires in Alain Kirili that reach ecstasy suspended in mid-air.

These are shamans: they have internalized the cry—il grido. The scream doesn’t dominate their range; to the contrary, their mouth smiles, like those of spouses on Etruscan tombs: and this is because their fundamental joy is able to digest the blackness. A blackness that they have, the same way we say a musician has a good ear, but which, for them, doesn’t get the last word.

This is conjure. That’s how I see Kirili’s statues, these elevations that salute the invisible; and that’s how I take in Lopez-Huici’s ecstatic portraits and sexual roar.

This game is never easy, as the demons are hungry and they will eat your life. The gesture Kirili and Lopez-Huici manage to accomplish is a sort of exorcism or counter- magic: they attack death itself, with forms that leap upward. Like Basquiat said, “Riding with death.” Riding on the back of one’s own death—the noblest of rituals.

Hence this smiling verticality, this defiance of heaviness, these excessive bodies, this outward push that ritually animates the oeuvres of Kirili and Lopez-Huici, and destines them to FOUND.

Indeed, foundation is what is happening here: the founding of a free space.

As I write this text I’m listening to a record that Alain spoke about to me one evening in New York: Max Roach and Anthony Braxton’s Birth and Rebirth. Pulsations of counter-magic, spells and counter-spells, freedom of space suddenly enlarged by music.

Immediately the name of Dionysus comes into my head, the god with bull’s horns, crowned with serpents, the dancing god—who cannot be bound.

And suddenly I think: Ariadne [Ariane] and Dionysus.

Each hears the affirmation of the other, and makes it the object of an other affirmation.

Life is not unworthy of being desired on its own account, and there’s no need to inveigh against it to make it livable; being two (or two together) clarifies what philosophy has labored to formulate: this couple affirms affirmation.

The Mysteries of Ariadne.

Dionysus carries Ariadne to the heavens; the jewels of Ariadne’s crown are stars. Reciprocally, Ariadne lavishes the clarity of erotic destiny upon the drunken god.

Thinking depends on the forces that take control of one’s thoughts. For Ariane Lopez-Huici, these forces are sexual. She has no fear. I can improvise a definition: Joy exists in proportion to the absence of fear.

The goddess according to Ariane dances with all-desiring eyes. She has the power of an eternally all-devouring little girl: this is Dalila. But she is also a river of hair swirling magnificently around a bust that’s been brutally severed: this is Priscilla.

For Kirili-Dionysus, verticality summons. The assemblages listen, the modeled clay calls out. Iron bars shaped at the forge, twisted iron wires, silhouettes of signs: these sculptures decompress the heaviness that is our common lot because they raise a voice.

Rising voices. Enlarging the horizon. Extension that founds itself. Open space for the great game of time.

Matter set into motion, launched upward, thrown into space, every more supple and spiraling, like a voice. These are gestures and soon they will be so light that Kirili’s sculptures will float in the air, like saxophone solos.

A surface shaped with rhythm, welcoming the arrival of the god.

Clearly, this god or this goddess is the opposite of religion (today religion is society itself): believing has nothing to do with it, much less joining.

This god is part of a deepening of the sacred itself through art; he offers himself in bursts even as he vanishes, slipping furtively between volumes, along curves, through interstices, whispering the pleasure that speaks the truth of being: he reminds us that there is someone, and that this someone is capable of loving.

For spiritual combat takes place at every moment. Not in the church, or in any place dedicated to liturgical servility; it takes place through bodies, voices, embraces—in the struggle between love and hatred, in whoever, at every moment, is separating light from darkness.

Here, finally, are Kirili’s Commandements. I’ve loved them for a long time. I don’t know where this gathering of small forms comes from. It’s as if these forms compose a burning text: Kirili himself speaks of an alphabet. They’re letters that burst forth from the immensity of languages, that carve up the babel of tongues and in its midst spread out their choreography of primordial writing.

Confronting the Commandements, one gets the feeling of a calm tabula rasa; one feels, in an obvious way, that things have hardly begun: we await the beginning, the origin itself has yet to occur, but it’s coming, it will happen: the origin is still coming.

It seems to me that I have always known this silent population that belongs to nothing but its own sense of expectation, that seems concerned with nothing but its invocation; and it seems to me that I have always been part of this millennial overflowing, that I have always recognized the voice that runs secretly through this field of atoms, this iron fervor, this extra-terrestrial material.

Free extension, where there is nothing we must answer to, where matter is left to itself, or in other words to the breath that turns it toward time.

If space takes place, as it does in Kirili and Lopez-Huici, this is not necessarily so that we can live in it: space opens itself in order to be born. Free spaces of invocation. Spaces of movements, where speech can move freely.

Breath of Kirili’s Commandements, that raise themselves up like so many vertical voices and mark off a space outside social coordinates: an entirely ritual cadastral map, whose very simplicity is part of an invocation, an appeal. A clearing, the opening of a region. A “speaking runway” [“piste parlante”], as Sollers has put it. A site for the advent of a god.

It seems to me that these Commandements have always existed, as if the Hebrew desert, ancient China, and the Dogon country of the Bandiagara cliffs in Mali, had all made this multiple rising possible—this population of signs emitting their immemorial gestures: an unconstrained space that opens onto the free voices of time.

This blossomed one morning on earth, far from countries or borders. It arrived by the hand of an inhabitant of this earth. It’s a memory that gathers, a memory that calls, that crosses surfaces, that now welcomes its neighbors plaster and iron, all of Kirili’s other works, but also these faces, these bodies, these Borromean spheres seized by the eye of Ariane Lopez-Huici.

So yes, it’s starting to come, and it’s coming from all over. To understand what happens when these photographs, these sculptures, and music come together, you need to be there, some night, at 17 White Street in Tribeca, NYC, where Ariane Lopez-Huici and Alain Kirili live, and experience one of the free jazz performances they arrange with musician friends.

The musician passes by, like Dionysus with his flute, and invents a voice that animates the sculptures and the images. This voice rises up, it opens a path, it founds.

Then there are no more photographs, or vertical terra cottas, or sounds; there’s no more photographer, sculptor, or musician: there is only a re-starting of time, an invisible vibration, a sort of embrace that mixes works and beings, a marriage, a smile: that of Ariane Lopez-Huici and Alain Kirili.

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Les Lutteurs, 2003, Alain Kirili, Ladder of dreams , 2003

( photos © Laurent Lecat )

Society as Cosmos

ON ARIANE LOPEZ-HUICI AND ALAIN KIRILI

by Carter Ratcliff, published in the BROOKLYN RAIL, May 6th. 2014

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Alain Kirili & Max, in their White Street loft, New York, 2008

(photo©Mathieu Bourgois)

VIE D’ATELIER

Entretien entre Alain Kirili, Ariane Lopez-Huici, et Marilia Destot

réalisé à New York le 06 novembre 2006, publié dans Mémoires de Sculpteur, Alain Kirili, éditions ENSBA, Paris, 2007

Marilia Destot : Je vous assiste tout deux, au quotidien, à New York, dans vos réflexions et recherches créatives. Une situation privilégiée de jeune artiste que je suis, au contact de deux artistes affirmés que vous êtes. Une position qui m'amène à suivre aujourd'hui l'évolution de chacune de vos oeuvres et la vie de votre atelier.

Dans le cadre de ce livre de témoignages que tu prépares, Alain, pour les éditions de l’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts, tu as souhaité pouvoir aborder la relation de ton oeuvre avec celle d'Ariane, développer la question du modèle et de l'enjeu du corps dans votre art. Également partager cette discussion avec moi, votre assistante, et artiste d'une nouvelle génération.

La sculpture d'Alain est abstraite-expressionniste, la photographie d'Ariane majoritairement figurative. Vous revendiquez tout deux une incarnation charnelle du corps dans vos oeuvres. Si l'incarnation du corps dans les nus d'Ariane est évidente, que signifie véritablement l'incarnation dans les sculptures abstraites d'Alain ? dans l'art en général ? Et comment dialoguent vos oeuvres dans cette incarnation partagée ?

Alain Kirili : Le mouvement d'art abstrait-expressionniste, par exemple la peinture de De Kooning et la sculpture de David Smith (1), est tellement incarné ! Le mot "incarnation" sera peut-être celui qui reviendra le plus souvent dans mon livre. Le corps est tellement présent dans l'oeuvre de De Kooning. Le corps est tout aussi présent dans son oeuvre figurative qu'abstraite : voici un exemple d'artiste qui peut traiter de l'abstraction et de la figuration, et dans les deux cas exprimer du charnel, une sensualité qui a un poids, une physicalité, qui a des os, de la chair et du sang.

C'est très caractéristique de cette intimité dans l’abstraction et la figuration que je ressens en permanence dans le dialogue avec l'oeuvre d'Ariane.

Ariane Lopez-Huici : Pour répondre à la question de la figuration et de l'abstraction, ce serait plus facile d'expliquer ce qu'est pour moi l'abstraction charnelle dans le travail d'Alain. Pour prendre un exemple que tout le monde comprend : quand on regarde un tableau abstrait de Mondrian tel que Boogie Woogie, il est certainement plus extactique qu'un nu frigide de Cabanel. Nous avons là deux artistes : un peint un nu franchement figuratif étudié très froidement, alors que l’autre tire des émotions qu’il a pu avoir en écoutant du Boogie Woogie, et traduit ses sensations de façon abstraite et vibrante. Avec Alain, c'est la même chose : ses émotions lui dictent son abstraction.

Je voudrais mettre cette conversation sous le signe de l'exuberance car c'est ce que j'ai aimé quand j'ai rencontré Alain, cette exubérance qui se traduit dans la vie, la vie commune que nous avons, ainsi que dans notre création artistique, dans la pratique de l'oeuvre de chacun.

Exubérance dans mon oeuvre qu'elle soit à ses débuts une photographie abstraite, mais qui avait des vibrations dans le traitement du noir, dans Oculus, ou dans In Abstracto, ou qu'elle soit devenue progressivement une photographie plus figurative, grâce à la possibilité de pouvoir m'adresser au modèle vivant. Exubérance alors dans le choix de mes modèles qui sont des modèles "autres" de ceux que l'on pense faire poser, des modèles "non-classiques".

AK : La photographie d'Ariane, près de mon oeuvre, donne des indications stimulantes. Des échanges se font depuis l'époque où elle photographiait des sujets abstraits, tels que des fragments de sculptures de temples Indiens, jusqu’à aujourd’hui, où elle photographie des modèles vivants. Oui, il y a une réciprocité, où l'un fait avancer l'autre, moi je le ressens comme ça dans mon oeuvre. J'aime lorsque je travaille être entouré de présences qui n'ont pas de rapport passif avec moi, mais des présences qui provoquent une émulation. J'aime cet aspect dynamique qu'il peut y avoir avec Ariane, ou avec une assistante comme toi Marilia, photographe d’une nouvelle génération.

MD : Cette présence est-elle justement ta notion du modèle, Alain, une présence avec laquelle tu échanges, comme un modèle poserait pour Ariane ?

AK : Ta question est importante. Dans mon travail, le modèle correspond en effet véritablement au mot que j'utilisais précédemment "la présence". Le modèle c'est une présence physique, je ne travaille jamais seul dans mon atelier. À l'opposé des abstrait-expressionnistes comme Barnett Newman qui comparait son atelier à un sanctuaire : atelier qui est en face des fenêtres du 17 white street, et dans lequel Newman travaillait strictement seul et dans le silence. Pour moi au contraire, c'est la stimulation d'un échange à deux ou à trois qui fait que j'ai une conception du modèle qui n'est pas traditionnelle : le modèle c'est l'autre, la présence de l'autre. Il prend le plus souvent la forme d'un assistant ou assistante. Le modèle est à la fois vibrations, intelligence, regard, conversation ; ce que j'appelle le “co-pilotage”, soit un dialogue dans l'évolution de mon oeuvre au moment même où je l'exécute.

MD : En partageant votre atelier, en voyageant ensemble, avez vous eu le sentiment d'avoir des périodes artistiques communes ?

ALH : À la différence de certains artistes qui travaillent en couple, qui créent en couple, nous avons deux oeuvres totalement différentes. Évidemment, il y a des intérêts pour les mêmes choses, mais elles s'expriment différemment. Une émotion, une force vitale primordiale nous conduit mais se traduit dans la diversité, Alain dans la sculpture, moi dans la photographie. En commun, il n' y a pas eu d'oeuvres faites à quatre mains.

AK : C'est d'autant plus important pour moi que j'aime bien l'idée que Sartre ou Simone de Beauvoir évoquaient : l'idée que dans un couple, il doit y avoir de l'espace pour deux personnalités. Je crois que c'est très important, et également vis à vis des générations plus jeunes qui travaillent avec moi. Je pense toujours avoir des relations de maïeutique : c'est à dire aider quelqu'un de plus jeune, quand il le souhaite, à devenir ce qu'il est, ou ce qu'elle est. Il ne s’agit pas pour moi de faire école, ou de créer une filiation. Ce qui est essentiel, c'est de se respecter chacun dans ces différences. C'est un des aspects que j'ai beaucoup aimé en vivant ici, à New York : les grands artistes qui me précédaient ont permis à des générations d'artistes différents d'émerger. C'est par exemple le cas de Rauschenberg et de Brice Marden qui était son assistant. Rauschenberg a contribué à ce que Brice devienne ce qu'il est. C'est une relation, une atmosphère que je veux dans mon atelier.

Il m’est arrivé d’exposer avec Ariane. Une exposition soulignait cet aspect de relations très différentes entre deux couples ; celui de Carl André et sa compagne Melissa Kretschmer, Ariane et moi, à la galerie Frank à Paris, en 1999.

MD : En développant chacun votre oeuvre, vous vous réunissez dans des passions communes pour certains artistes avec lesquels vous engagez séparément l'un et l'autre, des dialogues artistiques : Rodin, Picasso, Monet, Rubens, Goya, Cézanne, Matisse, etc... Je pense aux choix des modèles d'Ariane puis des poses, directement inspirés de ces peintures et sculptures. Je pense aux nombreux écrits et dialogues en sculpture et dessin d'Alain. Par cette passion commune pour ces grands maîtres, remarquez vous des correspondances concrètes, un vocabulaire artistique commun, un lien formel entre vos deux oeuvres ?

AK : Nous pouvons aussi réfléchir à ce rapport formidable de la photographie avec la sculpture, il y a un coté tres sculptural dans l'oeuvre d'Ariane, et ce qui m'intrigue Marilia quand on voit ton oeuvre, c'est la dimension picturale : le sfumato, etc... C'est çà qui est merveilleux, la photographie oscille entre la sculpture et la peinture, ce sont des dialogues, des observations, des échanges très riches.

Il est pour moi toujours difficile de verbaliser sur l'importance de ma relation avec l'oeuvre d'Ariane. Aujourd'hui, on ouvre quelques pistes.

Dans mon oeuvre, il y a par exemple une démultiplication des éléments pour former une sculpture. Je serais tenter de dire, que l'origine traditionnelle de l'idée de série pourrait se trouver chez Monet, dans la série des Meules, de ses Cathédrales, ou de ses Nymphéas, ou également chez Cézanne dans sa série des Baigneuses. L'idée de la démultiplication des corps dans la peinture Les Grandes Baigneuses, est une référence forte pour Ariane et moi. Ce tableau, qui est à Philadelphie, aux États Unis, anticipe une architecture de démultiplication de signes horizontaux et verticaux dans mon oeuvre.

J'observe aussi la démultiplication des corps dans l'excès de la chair à travers l'oeuvre d'Ariane. Actuellement, elle travaille avec quatre femmes, véritables statues, dans sa série photographique Les Géantes. Ariane pourrait en avoir encore plus, je sais qu’elle y pense.

Le lien entre l'oeuvre d'Ariane et la mienne, je le vois dans ces échos entre Les Baigneuses de Cézanne et les photos les Géantes d’Ariane, les Nymphéas de Monet et cette sculpture Commandement (à Monet) que je fais en ce moment pour le musée de l'Orangerie. Cette sculpture est une nouvelle démultiplication de signes en ciment coloré.

MD : Si vos oeuvres dialoguent aujourd'hui dans le même espace, le même atelier, elles sont en revanche conçues, dans l'acte final, à l'abri du regard de l'autre. Les séances de photographie d'Ariane, comme les exécutions d'Alain sont des moments de concentration intime privilégiés.

AK : Pour moi, l'atelier est une forge, donc ce n’est pas un lieu où j'habite. Le lieu d'exécution est éloigné du lieu d'habitation, et au moment de l'exécution, je ne peux être qu'avec mes assistants techniques, les forgerons, des assistants avec lesquels je travaille depuis de très nombreuses années comme Fred Crist. En revanche, l'autre atelier dans lequel nous visualisons les oeuvres dans leur phase finale, c'est bien le lieu dans lequel nous habitons et que nous partageons avec l'assistant. Cette interaction entre l'oeuvre d'Ariane et la mienne se développe dans notre lieu de vie. Mais je précise, lorsqu’Ariane fait ses photos avec ses modèles, je ne suis jamais présent ; c'est toute une relation très directe et intime avec ses modèles qu’il faut protéger.

ALH : Je voudrais revenir sur ce lieu unique : nous partageons un atelier qui est en même temps un lieu de vie, chose rare dans la tradition américaine. Si un couple d'artistes habite ensemble, ils vont bien souvent ensuite à leur atelier comme on va à son bureau. Pour nous, tout se mélange : le lieu de préparation, de création, de vie, on peut faire la cuisine, en même temps assister à la naissance d'une nouvelle idée. Je pense que cette idée de l'atelier qui rassemble la création et la vie est plutôt une idée européenne, ancienne, je pense que c'est un témoignage sur notre façon de vivre.

Ariane Lopez-Huici & Alain Kirili, White Street, New York, 2008-2013

(photos © Marilia Destot)

AK: Oui d'ailleurs je vais moi te poser une question Marilia : quel est pour toi l'apport de faire un travail avec moi ou avec Ariane ?

MD : C'est justement ce que disait Ariane, pouvoir être témoin de votre façon de vivre et de créer. Pouvoir être actrice aussi. Participer comme en ce moment même à une discussion et une réflexion sur l'art avec deux artistes est pour moi une incitation directe à réfléchir sur ma propre démarche. Comprendre et exprimer quels sont mes inspirations, mon propre vocabulaire, mes filiations artistiques.

Vous assister est une expérience inédite, et peu banale, puisque votre atelier est donc aussi votre lieu de vie. Ce qui fait toute la différence. Vous partagez ainsi beaucoup avec moi : pas seulement le travail et les décisions, mais aussi les moments de vie, les repas tout aussi inventifs et créatifs, les revues de presse matinales, les rencontres à l'atelier, les visites de musées, les concerts et “poetry reading” organisés ici.

C'est évidemment une expérience unique et stimulante. J'ai sous les yeux l'exemple d'une vie artistique riche et dynamique, toujours en mouvement, ouverte sur le monde, sur les autres, en perpétuel dialogue. Un modèle de vie et de curiosité permanente.

Votre exemple est d'autant plus important pour moi car mon travail d'assistante à vos côtés a coïncidé à quelques jours près avec mon arrivée à New York, avec mon installation dans cette ville, où vous vous êtes installés il y a trente ans, et avec mon choix personnel de me consacrer un peu plus à ma photographie.

Avec vous je suis "tombée" dans le bouillon artistique new-yorkais.

Justement, vous avez choisi de vivre à New York, une ville exubérante, cosmopolite, artistiquement effervescente, une ville dans un pays qui est son opposé : puritain, fermé, conservateur. La revendication d'une incarnation vibrante et charnelle du corps est-elle pour vous un engagement artistique comme politique ?

AK : J'ai souvent répondu à cette question, je voudrais simplement ajouter, que nous sommes dans un pays de la Réforme, et c'est ici même à New York que nous trouvons les esprits les plus rebelles. Il existe une conscience très critique des artistes originaires de ce pays de la Réforme. Une très grande lutte fait partie du dynamisme de cette ville.

Cette question est toujours d'actualité : on peut se demander si aujourd'hui on va être confronté à admettre ou pas une femme entièrement couverte de la tête au pied, si peut-être un jour toutes les françaises seront comme ça. Je lisais également dans le New York Times ces jours ci : une professeur de la banlieue de Dallas, a emmené ces étudiants voir le musée de Dallas, et 3 jours après s'est retrouvée licenciée car un des étudiants avait rapporté qu'il avait vu de la nudité, des nus au Musée de Dallas. On a appris par la suite que les fameux nus étaient des sculptures de Rodin et de Maillol. Et que la télévision locale qui avait rendu compte de l'événement avait montré ces "effroyables nus" en cachant les sexes des sculptures. Voici une anecdote qui je crois montre que les artistes de notre génération et de la tienne, sont toujours confrontés à la lutte pour la liberté, du corps, des expressions et des émotions. Cette exigence nous est transmise de génération en génération. Elle n'est jamais tout à fait acquise, il faut bien se dire que dans les années qui viennent nous serons obligés à résister à ces phénomènes de violence contre le corps, contre la femme, et nous serons gagnants ou perdants. Cela ne se négociera pas, il n'y aura pas de ligne intermédiaire. C'est à nous, à chacun d'entre nous de se passer le relais de génération en génération : à savoir que la délectation, le plaisir, la vie d'un corps, l'épanouissement des émotions, de la sexualité, cet enjeu dans la culture doit être protégé comme un signe de survie. Nier le corps, c’est entrer dans un dangereux nihilisme de la société. Cela a été vrai pour nous, et le sera jusqu'à notre dernier souffle, mais aussi pour ta génération. Le menace est constante. J’évoquais ce fait divers important, car l’on croit souvent que cette idée de violence contre le corps appartient au passé, alors qu'elle est dans le futur.

MD : Alain, tu parles de relais à faire passer de génération en génération. Je m'interroge sur l'incarnation du corps chez la nouvelle génération à laquelle j'appartiens. Je constate par exemple deux tendances opposées dans la forme et les thèmes : celle de la présence-absence de la figure humaine dans une esthétique poétique et mélancolique (telle que je la développe parfois dans mon travail avec le flou, des silhouettes furtives, ...) et celle de la virtualisation hyper-technologique du corps dans une esthétique souvent futuriste, surréaliste ou kitch. Sont-elles pour vous deux des formes de désincarnation du corps ?

AK : La sur-conceptualisation, si j'ose dire, pardonne moi la lourdeur du néologisme, qui cache la peur de l'émotion et de la sensation, est une forme pour moi de violence puritaine également. Son inverse, l'envers de la même médaille, la sur-représentation du corps dans un but commercial, comme marchandise et non comme noblesse dans la jouissance en "pure perte" est pour moi un phénomène de très grande violence également, qui s'accompagne par la dérision du corps. Pour moi le tout étant une représentation négative de le vie quelque part, en prenant évidemment toutes les précautions nécessaires qu'un tel sujet impose.

ALH : J'ajouterai que pour moi, toute grande oeuvre, que ce soit un nu, ou une oeuvre abstraite, doit provoquer un certain émoi érotique. Et si cet émoi érotique n'existe pas, il se peut qu'il soit remplacé par de la violence. Toute oeuvre doit quand on la regarde, au fond de soi-même, provoquer cet émoi érotique. Je me souviens avoir regardé cet été les Nymphéas de Monet avec Alain, et on se disait que ce qui était extraordinaire dans cette oeuvre, c'est qu'elle provoquait une émotion érotique. Et c’est là toute sa force.

AK : Évidemment, là nous sommes en parfaite complicité dans la recherche de ce mot très joli qui est la clé de notre profonde relation : l'émoi. Sinon on ne sait pas très bien à quoi sert l'oeuvre d'art. Non ?

MD : Effectivement si l'oeuvre n'interpelle pas ou ne provoque aucune émotion de quelque nature qu'elle soit chez celui ou celle qui la regarde, quel est l'intérêt ?

ALH : Je le dit pour moi, mais il y a des êtres qui ne peuvent avoir que des émois intellectuels. Pour moi la grande oeuvre, les grands artistes qui sont dans mon Panthéon ont suscité cette émotion érotique.

AK : Je parlerai aussi de cet autre lien entre nos deux oeuvres : la musique. Dans cet atelier, nous aimons beaucoup réunir des musiciens qui font une musique où le son a une physicalité, une qualité charnelle, un grain, une matière. C'est cette orientation de la musique contemporaine, celle du free-jazz contemporain, que nous aimons, parce qu’elle n’est pas formelle et prude. Marilia, tu constates avec nous que pour avancer dans la création artistique il faut se protéger avec des vibrations positives. La musique est de plus en plus dans ma vie, et celle d’Ariane, une complice de nos oeuvres.

ALH : Là encore je crois qu'il y a des correspondances, car ce que nous préférons, c'est évidemment le jazz d'aujourd'hui, qui est joué par des artistes de notre génération, en plus grande partie afro-américains qui ne sont pas effrayés par les émotions, par les corps, et qui essaient de les exprimer à travers leurs pratiques et leur art. Il y a comme ça tout d'un coup une camaraderie, une famille, une émulation qui poussent tout le monde vers le même désir : celui de sauvegarder l'émotion. Tu le fais toi-aussi Marilia dans ta photographie.

Tant que l'émotion prime, nous sommes sauvés.

(1) Alain Kirili a présenté un choix de dessins de David Smith, à la Chapelle des Petits-Augustins, l’École Nationale supérieure des Beaux Arts , du 18 mars au 27 avril 2003.

Ariane Lopez-Huici & Alain Kirili, White Street, New York, 2007-2013

(photos © Marilia Destot)

Carnet nomade, caméra bougée de Soho jusqu'à Brooklyn

Rendez-vous chez Alain Kirili et Ariane Lopez-Huici, New York, Dimanche 17 février 2008

par Colette Fellous, France Culture,

Alain Kirili et Ariane Lopez-Huici, in their White Street loft, New York, 2013

(photo©Marilia Destot)

Au sujet des photographies le triomphe d’Ariane

“ J’aime bien leur aspect qui se relie au baroque et qui sont aussi les qualités formelles de la photo. C'est ce côté où la chair dans ses plis soutient un effet de tournoiement. On voit bien dans cette colonne de femmes, ici de leur chairs, ce n'est pas seulement la forme du corps, c'est aussi les plis du corps, les plis de la poitrine, les plis du ventre qui favorisent ce tournoiement dans l’espace j'ai l'impression.” Alain Kirili

“Oui, c'est tout à fait ça. Je crois que ce sont les mouvements, les plis, la chair. : reprenons contact avec notre chair, avec le désir, ne pas avoir peur d’exposer. ” Ariane Lopez-Huici

White Street studio view, New York, 2008-2013

(photo©Marilia Destot)

“L’INCARNATION DE LA CHAIR ET DU CORPS”

“UNE PASSION COMMUNE POUR L’EXPRESSION DE LA VIE”

Ariane Lopez-Huici et Alain Kirili échangent sur leurs oeuvres photographiques et sculpturales respectives, extrait du film Alain Kirili, Sculpteur de tous les éléments, par Sandra Paugham, 2009

White Street studio view, New York, 2013

(photo©Marilia Destot)

White Street studio view, New York, 2013

(photo©Marilia Destot)

White Street studio view, New York, 2013

(photo©Marilia Destot)

Alain Kirili & Ariane Lopez-Huici,

A Life Together

Dedicated to Art and Creation

A Conversation with Ariane Lopez Huici, June 2024, New York

Recorded and edited by Marilia Destot

Marilia Destot : My dear Ariane, like you I am also a French artist who came to live in New York in her late 20s, and as a close friend and assistant to Alain, I was fortunate to spend time with both of you in your loft in New York. I always considered your couple and artistic lifestyle a unique and marvelous example, a true inspiration for what life can be when two artists leap into the unknown together, supporting each other’s creative work, and generously sharing their enthusiasm, curiosity, and art space with other artists.

To begin our conversation about your shared life dedicated to art and creation, tell us a little bit about how you and Alain met.

Ariane Lopez-Huici : I met Alain in 1976 in Paris at the Ghislain Mollet-Viéville Gallery, across from the Museum Pompidou. Ghislain was exhibiting American Abstract artists, such as Robert Grosvenor and Marcia Hafif. There was a young man in jeans, a little bit dirty, who Ghislain presented to me as “Alain Kirili, a sculptor.” Alain started speaking with me, we had a good connection, and he said he hoped to see me again. The funny thing is that same night there was an opening for an exhibit featuring Russian constructivists at the Jean Chauvelin Gallery, in place Furstenberg in the Saint-Germain neighborhood of Paris. We run into each other by pure chance, and Alain, with his usual enthusiasm, once again expressed his desire to see me. So we met a few days after and we had a little affair. And then one day he told me “I'm going to New York, why don't you come?” And he called me every day to ask “when are you coming? When are you coming?” I thought he was so enthusiastic. So I went.

Alain was staying with an artist friend, Lucio Pozzi, who had a studio on Greene Street in Soho in 1976. I must tell you, Soho was deserted at the time. I arrived, rang the buzzer, and no answer. Shoot! What should I do? Back then we didn't have cell phones. I went to a nearby bar, Magoo's or another place nearby. I kept calling and after an hour he finally answered and said “you know what? I'm here.” He was very sorry. He said “come quickly.” So I came and he said “I have a surprise for you. I bought you cheesecake from Eileen’s.” I hate cheesecake, should I tell him that I hate cheesecake? Otherwise, I will have to eat cheesecake the rest my life. So I told him “I hate cheesecake.” So he closed the cheesecake box and we went to see all "his copains.” I guess he wanted to introduce me to his friends, to get their approval. We went to see all of his male friends, and after the second or third day, his friends told him, “look, if you don't take her, I will.” So Alain told me, “I'm not going to introduce you to any more of my friends.” After ten days, I went back to Paris, and that’s how it started. Voilà.

MD : A great start. What amuses and amazes me, is the place you first met: an art gallery. Ariane, you were already an artist too. How do you think that this artistic context drove your future life together as artists?

ALH : This is a very important point. I had just finished being an assistant to a great movie director, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, who is known as the father of Cinema Novo. I spent five years taking a lot of photos on stage, I already wanted to become an artist. Or if I couldn't, at least to be with artists. And Alain really encouraged me to follow up and devote myself to photography. Being together, being artists together can be a challenge. I never thought that my life with somebody should be a battle at home. Being both artists was never a conflict, especially because I was a photographer, and Alain was a sculptor. So we were lucky. And we had a good marriage for 40 years.

MD : So you came to New York in 1976 to meet Alain, but how did your life together in New York really begin?

ALH : We met in 1976 in Paris, again in New York, and we got married in Paris in 1977. Alain was exhibiting with Ileana Sonnabend in New York, and we would visit New York by exchanging apartments. When a New York artist wanted to come to Paris, we would swap our place for theirs. I remember that for six months, Kirk Varnedoe conducted research on Rodin at the Musée Rodin, so we swapped places. This lasted for a while, but one day Ileana told us, there is a building that is going to be converted on 17 White Street in Tribeca. Tribeca was not called that at the time. It was called “below Canal Street,” and I must say that uptown New Yorkers didn’t know where it was. They would say “below Canal Street? Is it still New York?” In 1977-1978, below Canal Street confused people more than anything. Anyway Elizabeth Murray had her studio in that building, it was illegal, so the whole building had to be converted into artists residencies. The fourth floor where we lived, and where I still live and where we are talking now, was squatted by Jan Groover, a photographer who was exhibiting with Ileana Sonnabend. Jan and her husband Bruce Boice didn’t want to go through the hassle of converting, because first of all they loved to smoke and drink. And at that time in America, laws were being passed banning smoking in restaurants. So they decided to leave and move to the Périgord, among the vineyards, so they could drink and smoke. So we took their space, which is a wonderful space, one that we could use both to live and to work. So that’s how we started our life in New York, having this place of our own and then asking for a visa, a green card, etc. in 1979. It's history.

MD : Tribeca wasn’t Tribeca yet, as you said, but was it home to a vibrant community of artists at the time?

ALH : Not yet. Soho was more the place to be for artists. But Soho was already too expensive for us. Below Canal street was where some artists had their working space. Across from our loft on Church Street, on the third floor, there was the studio Barnett Newman used in the 50s. Tribeca was more of a place for printers and small businesses. When we came, there was a guy who was just selling eggs. Voilà, it's how I remember that time.

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Alain Kirili & Max, in their White Street loft, New York, 2002

MD : That reminds me of this lovely moment filmed by Camille Clech in this same Tribeca loft in 2021, where Alain and you are talking about your wonderful trips to Paris or Italy. While New York was certainly the primary location of your life together, I also think about all of the beautiful trips you made together around the world, with each journey being very important to your creation. Some of the more iconic trips were to India, Mali, Sénégal, Cambodia, Italy, and of course France. They’re not the typical tourist visits, as each one was imagined in connection with a very specific artwork, temple, sculpture, or painting to be discovered, or even rediscovered. Could you tell us about the first very important trip you made with Alain, to India if I remember correctly?

ALH : It is true that with Alain, travelling was mostly about art.

We went to India on our honeymoon. I was from the generation that thought “why get married?” Especially for a woman. I remember Simone de Beauvoir saying “who gets married nowadays? Only priests.” So I was a little bit reluctant. I was independent and didn't see the urgency in getting married. But Alain was adamant. He told me “Ariane, if you are committed, you have to be committed in life. And if you love me, and if you want to be with me, you have to commit and get married.” So we got married, and I told him I wanted a very exceptional honeymoon. And he said, okay, you choose. So I pointed to India on the world map because I’d never been there. It was far away and very complicated to go at the time. We went to northern India, Rajasthan, Kashmir and Nepal, Kathmandu.

We went from Delhi to Rajasthan, to the famous erotic temples of Khajuraho. They were rediscovered in the jungle, a hidden location where the sculptures have been preserved for centuries. The prudish British didn't see them and didn't destroy them. The Muslims didn't destroy them either because they did not find them. So we saw those incredible temples with unimaginable sculptures of the Kama Sutra. It was very nice because the Indians were very proud of the temples. They would come with the whole family, to look at those sculptures with their children. There was no problem.

So yes, during our travels, we were always looking for art. We traveled mostly for art. During our travels in India, we encountered something that we had never seen before: the famous Yoni-lingam. Yoni-lingams are the abstract representation of Shiva, with a phallus and a base like a vulva, representing the power of creation. It’s a very sexual representation, and they are all over in India. It's like the cross in Western civilization.

Alain started to be very interested in them, and took a lot of photos. He even “converted for that occasion" to Shiva because he wanted to go to the temple. Each time he was asked “are you a worshiper of Shiva? Are you, sir?” he would respond yes. And the Indian thought “are you desperate? You come from a Christian world, how could you be a worshiper of Shiva? We are so sorry for you.” Alain told them “this is magical to me, worshiping the Shiva Lingam is very poetical to me, your rituals are splendid.”

We made many trips to India.

In connection with our Indian travels, we also went to Angkor Wat in Cambodia, with its incredible Khmer temples, and once again numerous Lingam, hidden underwater or in fields.

MD : I know you loved returning multiple times to see a temple in India, a painting in Florence, a sculpture in Rome or Burgundy. Could you tell us how those travels inspired you? How they were a true essence of your common and creative life?

ALH : The reason we went to those places is firstly because Alain thought being a contemporary sculptor didn't mean being oblivious to art history and the work of your predecessors. He really wanted to look face to face with the past, look at the masterpieces of past centuries in Europe, Africa, and Asia.

For instance in Italy, when we went to Rome, it was to see Bernini’s sculptures, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa in the chapel of Santa Maria della Vittoria, or Caravaggio’s paintings at the San Luigi dei Francesi church. We went to Florence to see Michelangelo’s David and Donatello’s Penitent Magdalene, also to visit the church of Santa Felicita, with its masterpiece, Pontormo’s The Deposition from the Cross. From Florence we went to Volterra to see Ombra della Sera, an Etruscan statue that inspired Giacometti. So you see, from Etruscan art to Giacometti and Kirili there is one “royal path” of creation.

We also went to Milan to see Michelangelo’s last work, the Rondanini Pietà. And of course we went to Venice, because it is an open air museum.

In France, we really wanted to see the cathedrals, the romanesque and gothic churches, inspired by Rodin’s book The Cathedrals of France. And when we were traveling to those towns, some smaller and some larger, we would always try to find a typical French restaurant, and local delicacies. For instance in Rouen there was this incredible Restaurant La Couronne, where they invented le canard au sang.

Another major sculpture that Alain enjoyed was The Mourners of the Dukes of Burgundy in Dijon. They were a major inspiration. His sculpture Cortege from 1982, which was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art early on, was probably inspired by those Mourners. When we were in Dijon we would visit our friends Pamela and Aubert de Villaine, and their Domaine in Romanée Conti. Another treasure of our French culture.

Overall, it was very important for Alain to remember, to connect his creation across different periods and cultures, to acknowledge these sources of inspiration and stimulation in creative dialogues.

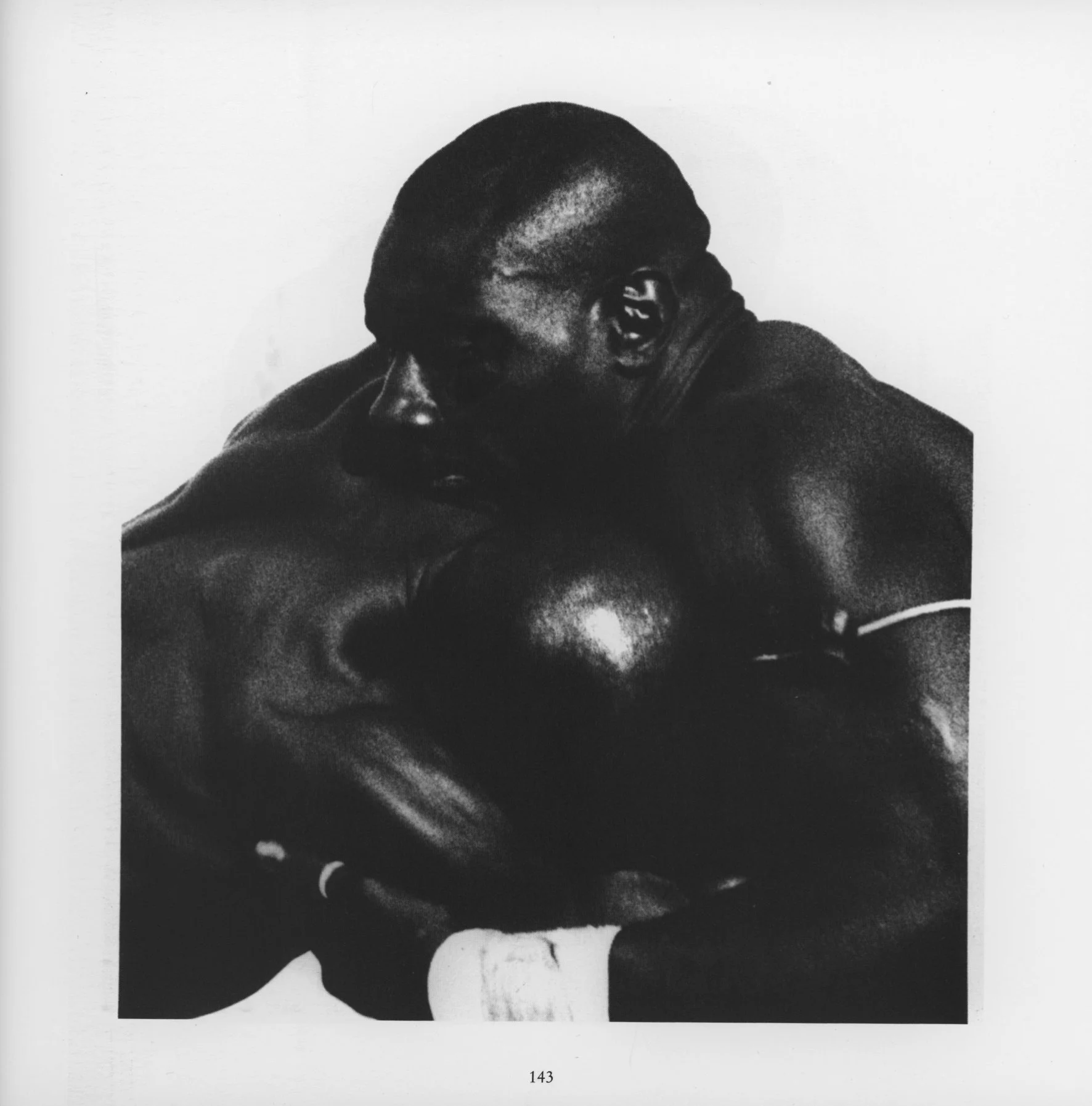

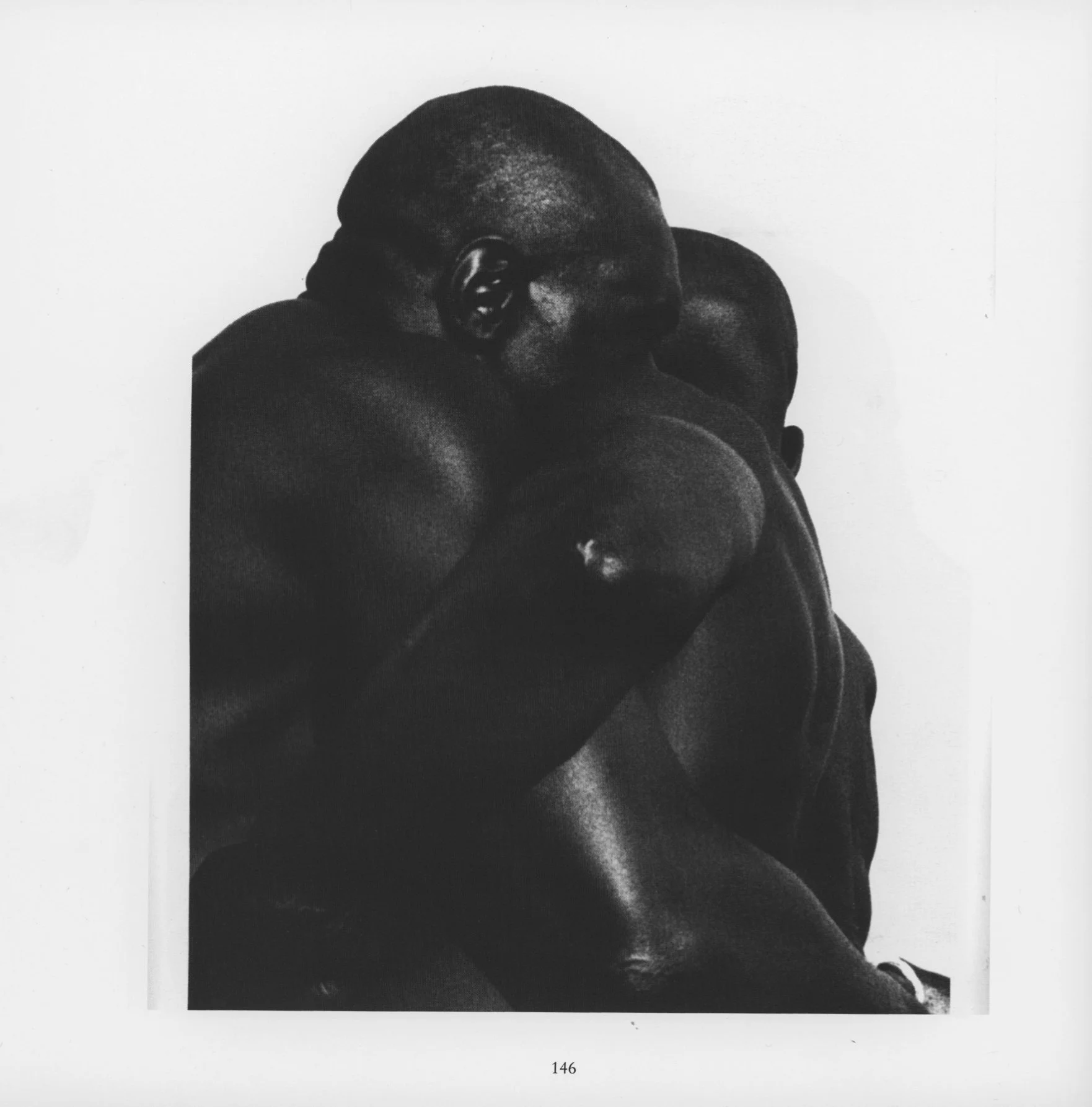

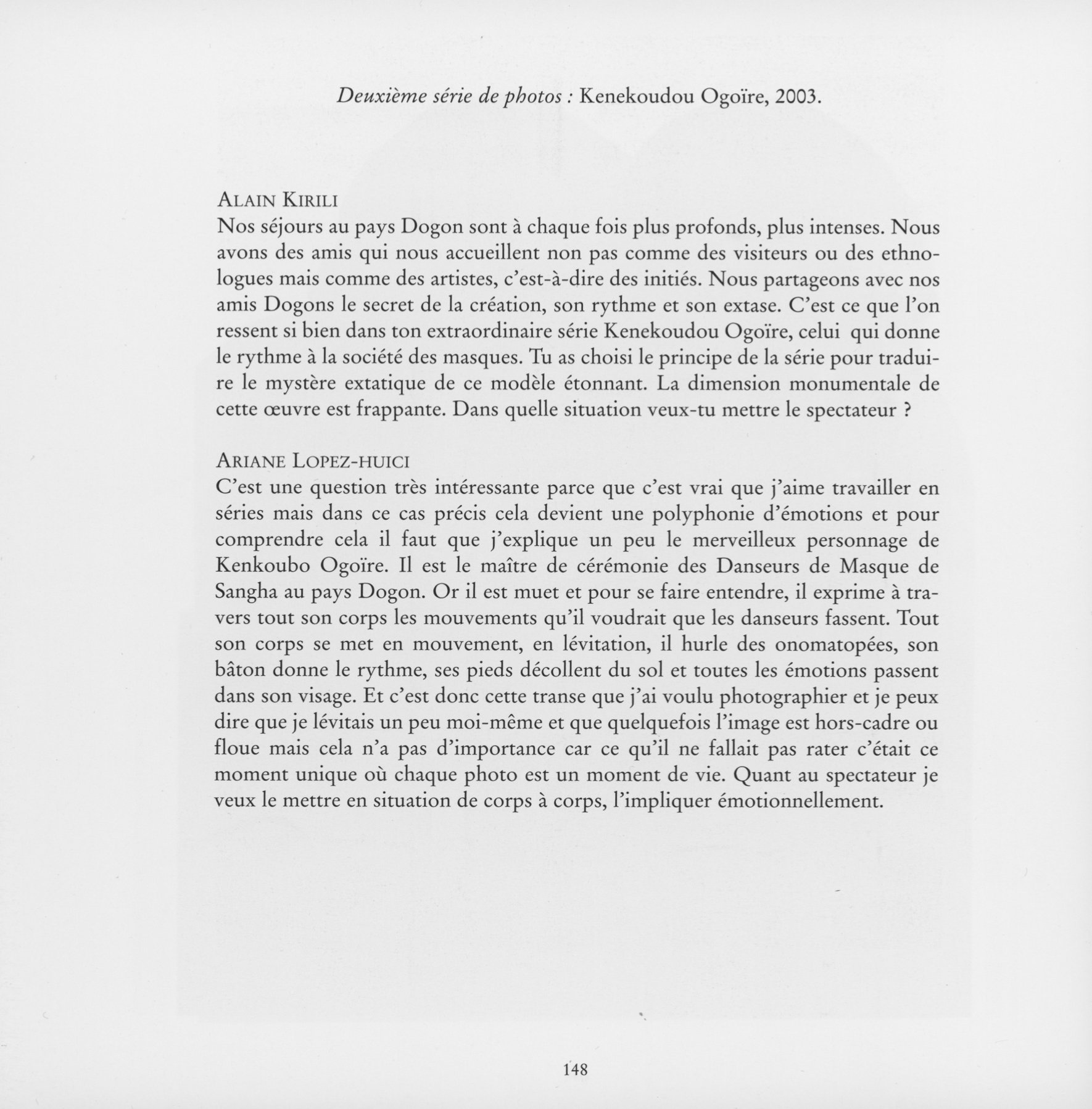

MD : What about Mali ? That was another very important place for you and Alain. You photographed various series such as The Wrestlers Adama and Omar, The Master of Ceremony Kenekoubo Ogoire, The Demoiselles de Segou. And Alain forged his Ségou series in Dogon Country.

I know that you shared this desire to create driven by the unknown, by the spontaneous encounter. You obviously each created your own work, using your own models, inspiration, and mediums, but always encouraging and stimulated each other’s artistic development. A bond that grew over time, and over the course of your travels.

What memories can you share with us about your travels and creations in Mali?

ALH : The first time we went to Mali was around 2000.

At that time in Paris, we were invited to go to the Bouffes du Nord to see Antigone by Peter Brook with a Malian cast. We became friends with Sotigui Kouyaté, Peter Brook’s favorite actor. They convinced us to go to Bamako, where we met the two great photographers, Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibé, the musicians Ali Farka Touré and Toumani Diabate. We also met the Dogon sculptor Amahiguere Dolo, who invited Alain to come to Ségou and work in his studio. From there we went to the Cliff of Bandiagara, in Land of the Dogons. In Dolo’s studio, Alain created several sculptures that he called Ségou, which were exhibited in the garden of the Palais Royal in Paris. In 2005 we also organized, at the French Institute of Bamako, a performance with African-American jazz musicians—Joseph Jarman and the baritone Thomas Buckner—the dancer Maria Mitchell, and Dogon dancers. We went several times to Mali, Senegal, and Burkina Faso.

Now about my own creation, it was very productive because I was always interested in those expressive bodies. For The Demoiselles de Ségou, it was very difficult to convince Malian girls to pose nude for me. So I had an idea. I thought to myself “there must be a brothel in Ségou.” So I asked and I was indeed taken to one. In anticipation, I brought a lot of little Chanel samples, lipstick and perfume. At the brothel, the women were of course not from the village of Ségou. They were not even from Mali. They were from another ethnic group, from Burkina Faso or Senegal, so no-one from the family would know about that. Thanks to the lipstick we became friends and had lots of fun, they were very happy to pose for me. They were wonderful Odalisques. I also met and photographed the master of ceremonies Kenekoubo Ogoiire, who led the Dogon dancers. What was extraordinary was that he was deaf, he couldn't speak. So he had this way of expressing and leading the dancers just with his body, he would jump and the dancers would follow him. I mean, it's such a beautiful story about bodily expression, one that I found very interesting. For The Wrestlers, I had this idea of photographing wrestlers because I was familiar with Senegalese wrestling. So when we went to Senegal a friend took me to the poor area, where children start to learn this famous wrestling at an early age. I sat on the sand and started to watch them. And then people understood that I was not a paparazzi or whatever, I just wanted to record the beauty of their wrestling, and so they participated in it. Senegalese wrestling is very interesting. No punching is allowed. No violence. It’s more like a wrestling dance. The winner is the one who can turn the other on his back. The wrestlers are very famous, they start at a very young age, around five or six years old. It’s very beautiful to watch.

I remember exchanging anecdotes about our sitters in our studio, Malick Sidibé telling me that the women in Bamako would put on perfume before posing...

Alain and I liked their way of living, adapting to a modern life, but keeping their ancestral traditions alive. Living in a puritan society such as the United States, it was very comforting to witness that in Mali, there was no war between the spirit and the body. The Poet/Griot was at the top of the pyramid. Poetry and art were considered the most sacred values in the Dogon tradition.

MD : Back here in the setting of your New York loft, I think of another important element of your identity with Alain: “l’art de vivre.” Of course it comes from your French culture: cooking well, eating, drinking, sharing a lively discussion around a beautiful table. Maybe mixed with the New York culture of opening your loft and welcome other artists. Can you tell us how it was essential to your life as a couple and as artists, not keeping the place where you lived and created separate? Sharing it instead.

ALH : Dear Marilia, this is a crucial question!

My generation of women rebelled against the idea of cooking. But my grandmother, who was already in her 90s, told me: if you want to keep a husband, you have to prepare delicious dishes. So when we moved to NY, and to keep with our French tradition, I started cooking and preparing delicious meals!

I was always intrigued by what artists would eat. For example the writer Karen Blixen survived on Champagne and asparagus. Brancusi was a great cook. Tell me what you eat and I tell you who you are!

Eating, drinking, and everything in between was fundamental to our creation. And our African-American musician friends were the same.

When I asked Sunny Murray if he would eat frogs he said: when you are born poor in the South you eat whatever you catch! And Cecil Taylor was very proud to say his father was a cook.

So it is true that I cooked and hosted a lot of meals, it was always a pleasure to share with friends. I guess I had some success, and when I meet old friends they always talk about the dishes I made. Alain and myself, we liked to be surrounded by friends.

And, as you know, what was also essential to our life was our relationship to jazz and experimental music.

Alain was an aficionado of jazz since childhood, when he met Sidney Bechet in his parents’ kitchen. Thanks to a dear friend Nadine de Koenigswarter, who is the granddaughter of the Baroness of Jazz Pannonica de Koenigswarter, in Paris we met the Saxophonist Steve Lacy. He introduced us to Cecil Taylor, and we bonded immediately. From then on, we organized many collaboration with CT, Steve, and other musicians from the world of free jazz: Steve Lacy and Roswell Rudd with Kirili’s sculpture in the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, and Cecil Taylor & Kirili’s sculpture at La Cité de la Musique, to name two of many.

Aside from these numerous performances in specific venues, museums and galleries, we opened our loft and programmed what we called the "Loft Series”: here in our Tribeca loft, and in the rue Rodier studio in Paris, we would invite musicians to interact with visual artists and poets.

These live improvised creations in our loft and elsewhere were an essential part of our life, an essential part of our “art de vivre.”

MD : Ariane, to conclude this conversation, what would you say were the key moments in your life with Alain?

ALH : Marilia, if you ask me about key moments from our life, I will tell you of course our marriage and our emigration to New York. Not having had children, our life was dedicated to art, to our creation as it unfolded over the course of our exhibitions.