Kirili in Dialogue with

Carter Ratcliff

American poet and art critic

Carter Ratcliff, reading his poetry with Alain Kirili’sculptures,

White Street, NY, 2009 (Photo © Ariane Lopez-Huici )

“In reading the tributes to Alain, I was happy but not surprised to find such a high degree of unanimity. As his friends say, he was charming, sophisticated, and brilliantly creative. He was generous not only to other artists but to musicians, dancers, and poets. He believed in high culture, not as a marker of superiority but as a down-to-earth good that he and his wife Ariane Lopez- Huici did their part to make available to everyone. Though this is not a complete list of his lovingly remembered virtues and talents, I would like to focus on one that was mentioned only in passing: Alain was an impressively original writer.”

Carter Ratcliff

excerpt from A Tribute to Alain Kirili, edited by Robert C. Morgan and Carter Ratcliff, in The Brooklyn Rail, November 2021

Carter Ratcliff reading his poetry, White Street Studio, New York, 2006

(Photo © Marilia Destot )

The Sculptural Body, Alain Kirili

by Carter Ratcliff

published in Sculpture Magazine vol 27 n4, May 2008

Alain Kirili, Carter Ratcliff and Ron Gorchov

at Alain Kirili’s studio in New York 2009

to prepare the duo show Célébration de la Main

at the Galerie Richard, Paris, 2009

The Animating Hand :

The Art of Ron Gorchov and Alain Kirili

by Carter Ratcliff

published in the exhibition catalogue by Galerie Jean-Luc & Takako Richard, 2009

« The Animating Hand » : this is what two artists offer you at the Galerie Jean-Luc & Takako Richard through December 30th. If Alain Kirili and Ron Gorchov both celebrate the hand, they each celebrate it in their own manner, one being a sculptor and the other a painter.

duo show Celebration de la main: l'art de Ron Gorchov et Alain Kirili, Galerie Richard, Paris - 2009

The French artist (Kirili), who lives and works in New York and Paris, shows that his hand possesses more than savoir faire. The exhibition is split between forged iron sculptures, modeled clay pieces, drawings on tracing paper, and paintings (gouache, watercolor, ink) on paper. Whatever the chosen technique, the artist has ambition, and he succeeds in reworking space by the positive and negative space confront each other. Another characteristic that can be spotted immediately is the energy put into this work. A video showing that artist at work confirms this(1). It requires an incredible amount of energy to throw one piece of earth into another before squeezing and encircling it as he does. Strength and enthusiasm are necessary to hammer iron with a sledgehammer (2). Even drawing expressively on paper requires the engagement of all the power within the artist’s body. If his body lets itself be taken away by the force and repetition of his actions, his critical judgment remains present; his spirit awakens and controls the result. While not essential to sculptures, color is not missing from his. Some iron pieces are painted in white, others dressed in red. In the blocks made of clay, red ochre glides into the gray, green lets itself be enclosed by brown. The visitor appreciates the diversity in these approaches, his avid gaze could either lose itself in the dips and trenches built into the clay sculptures, or endlessly bounce off of the facets of the hammered iron works.

The use of forging on sculpture is not very common. There is a strong desire in his creations to destroy iron’s impersonal, industrial form and make it into something more human. The titles of certain pieces confirm it: Adam I, Adam II. The indents resulting from the forging are at the same time places that welcome the visitors gaze and concavities that reflect it back in multiple directions. This characteristic (reflecting back one’s gaze) asks the viewer think about how optics affect the comprehension of a sculpture. Looking at it does not suffice. It is in front of these types of pieces that we can use other senses as well, and that is just what is proven here. Alain Kirili succeeds at giving each one of his sculptures not just visual qualities, but also tactile ones. The artist’s ability to think about the visual through the tactile is particularly evident in his hand-modeled pieces. The clay works are receptacles of force. The viewer feels the pressure of the artist’s palms and distinguishes the impressions made by his individual fingers. The apparent joy of the martyred piece intrigues the viewer, and he wonders about the first scene. What original accident led to such sensual metamorphoses? The piece of art, that big mute, doesn’t give the answers; they are of course unique to each sculpture.

Alain Kirili’s sculptures, more than any others, create their own space. The space in which they are placed is no longer neutral, it becomes a place of converging forces (3). The forged iron sculptures invite interaction. These interactions go through the eye, it is after all a visual art form, and in some cases activate corporeal reactions in the visitor. These sculptures are invitations to other bodies. As the video about the artist shows, he sometimes invites dancers to examine the plasticity of their bodies with his works, or sometimes he invites jazz musicians to envelope them in their syncopated rhythms (4). These moments of contact with the pieces bring them back to their genesis. While these plastic productions (iron, clay, drawings) are mute and are generally contemplated in silence, their creation was accompanied by specific noises coming from the rustle of the coal to the rhythmic sounds of striking the hot iron, passing through the dull sounds made by a piece of clay as an energetic gesture throws it against another. One can still hear the dull and contained groans of the clay in the titles of these sculptures: A-da-mah, A-da-mah, A-da-mah… and the short, powerful cries of the iron at the moment it is struck. As Tom Mitchell recently said: “Pure vision attaches itself to the entire spectrum of senses, particularly the sense of touch (5).” This multi-sensual aspect of Kirili’s work helps with their translation. Like in the case of the dancer, who interprets the sculpture through improvised movements that translate the artist’s creative gestures – those of his hands, arms, and legs, all connected at a central point in his back. That’s where it hurts. Acknowledging this exquisite pain allows the artist to hope to infuse the work with an authenticity that can become a source of acute joy for the perceptive viewer.

Kirili is a man of fire. There is always something that ignites in him, whether he is speaking or creating art. This is evident in the generative gestures of his work. The iron knows the forge’s fire before it takes shape; the clay gain their strength and final appearance after being fired; the primary element in his drawings and paintings is charcoal made from burnt wood. This artist is not a sculptor who removes material, he prefers to add it. A clay becomes trapped inside another (Adamah IX, 2008). After modeling, each piece of iron tends to become associated with another. The relationship can be functional like when a modeled piece of clay serves as a pedestal (Adam I, 2009) or when a another piece of iron increases the ways in which the sculpture can stand (like in Equivalences IX, 2009) but the relationship can also respond to an aesthetic problem. Thus the simple juxtaposition of seven iron bars (Funambules VII, 2008), placed parallel to each other leaning against the wall, proves to be very effective.

Back to the marks: the clay and iron materials have preserved the marks of human action, like memories of the action, of actions done by the hand of man in another time. One of the attributes of photography is its ability to capture a moment in time with a ray of light. These works, which we could call chirographic (6), are interesting in part due to the time trapped in the material just as the artist wanted it. Why did he put that indent there and not just in front of it? Simply because it relates to the sensibility of the sculptor at any given moment. He creates a stop, a voluntary stop, a completion in the unfinished. Like Giacometti, whom he references, Alain Kirili is careful of this completion. He avoids the smooth as much as he does the stopping the eye’s path. One’s eye does not glide over his sculptures, it bounces off and, on the long stem of Forge I (2008), the feeling of repetition approaches the same sense of movement and height seen in the endless column by Brancusi.

Sculptural infinity is, without doubt the quest Alain Kirili has been pursuing for years.

Though they are abstract, Ron Gorchov’s paintings keep the body as a reference point. The paintings strengthen their presence as body-objects by the presence of a stretcher that doesn’t try to hide its handmade quality. This stretcher, with its thickness (between 14 and 38 cm) and its curved shape serves as the support for painted linen canvas, simply stapled on. Pairs of colored forms are painted on these canvases. Two opposing spatial considerations present themselves: from the front they take on the illusory spatiality of painted objects, from the side the singular volume of the support structure draws the viewer’s attention. One realizes that Ron Gorchov, in launching himself into the shaped canvas, wanted to shake up tradition: the surface of a painting does not need to be rectangular – here all the corners are rounded – and it does not need to imitate the flat wall on which it is hung. These non-canvases (7) acquire a certain presence, a pseudo human presence, in the space where they are displayed which catches the viewer’s gaze.

The canvases are painted in successive strokes of color. A subtle balance between the weak presence of the pictorial material – the transparence of the paint leaves the canvas underneath partly visible – and the intensity of the colors. Yellows, reds, and blues are always supported without being bright, go well with the clay sculptures. In the center, like on the edges, the brushstrokes remain visible. In Gorchov’s work, plastic subtlety finds itself in the limits, the limits of the shapes just as much as the limits of the canvas on the stretcher. For each color, the visible brushstrokes mark the minute differences in tone. Each painting represents only one figure, constituted of a number of abstracted painted shapes. In this rarefaction of marks, all the small stray brushstrokes gain added importance. As some painters know very well, such as Mark Rothko, the use of tiny variations can prove to be source of great pleasure. Here the painted shapes have been stripped of all metaphysical sense. They are visual facts, nothing is really more important than that. These works frustrate because they are impossible to interpret. The object is nothing more than a painting (stretcher and canvas) without becoming necessarily something else, like a shield. The figures painted on the canvases stapled to the stretchers are intermediaries between allusive human figures and architectural representations. Their centrality in the paintings may evoke faces; their silhouettes may evoke the ghosts of actors evolving on stage. The creation of these images does not seem to have stirred any lasting effect. They are painted, neither well nor badly, simply painted by a human hand. These non-paintings welcome the figures left unfinished in an intermediate state. The artist avoided perfecting them in order to avoid killing them.

Alain Kirili invited Ron Gorchov to join him in this exhibition due to their longtime friendship and also to examine the differences that appear in their creations. The sculptor, even though he produces drawings that are precisely the drawings of a sculptor, invites the painter to occupy the walls of a gallery at the same time as him. A prolific and sensual artist welcomes an older, more reserved and discreet one. One like the other works in sincerity. Their works are neither visually nor spiritually fake. Things are depicted as they are. Iron branches and clay blocks on one side, painted objects with colors put on them on the other. The other essential characteristic of this exhibition is announced in the title: the animating hand. Even if, as we have seen, things don’t stay there and lead t other celebrations of other senses and above all the spirit, here everything is made by the hand of man, and is presented as such. Nothing that defines this genre is missing: inventive manufacture, sensitive qualities of the pieces, diversity of the results. These works of art, without literal images but not without evocative shapes, open multiple imaginative possibilities. Whether bright or calm, the forces in place here go, via the tactile, to touch on a global sensibility. It is because they were touched that these artistic creations touch us in return.

Carter Ratcliff, 2009

(1) Alain Kirili, sculpteur de tous les éléments de Sandra Paugam, collection « À contre-temps », Groupe Galactica.

(2) Even if the exercised pressure can be the one of a machine, it is necessary to hold the bar of raw iron and to hold it hardly.

(3) A few iron forged sculptures (those titled equivalences) can be arranged in various manners: raised vertical or put horizontally, placed in the center of a space or rested against a wall. The vision changes and the evocations suggested also.

(4) The title of Alain Kirili’s monumental sculpture settled in 2007 in Paris, Espace Masséna, in the 13th district, is Tribute to Charlie Parker.

(5) Tom Mitchell, in ” what want the images? ” Crossed Interview with Jacques Rancière, led by Patrice Blouin, Maxime Boidy and Séphane Roth, Art press n° 362, p. 34.

(6) Word builds on the model of “photograph”, here the kept tracks are not any more the ones provoked the light but those left by the action of man’s hand. The Greek word for the hand to kheir looked in chiro French.

(7) The non-flatness of these works does not predispose them to be tabula (boards to be written) and some more surfaces on which we can put objects or dishes of tables). No relationship with the bulletin board is wanted and the artist goes away voluntary

duo show Celebration de la main: l'art de Ron Gorchov et Alain Kirili, Galerie Richard, Paris - 2009

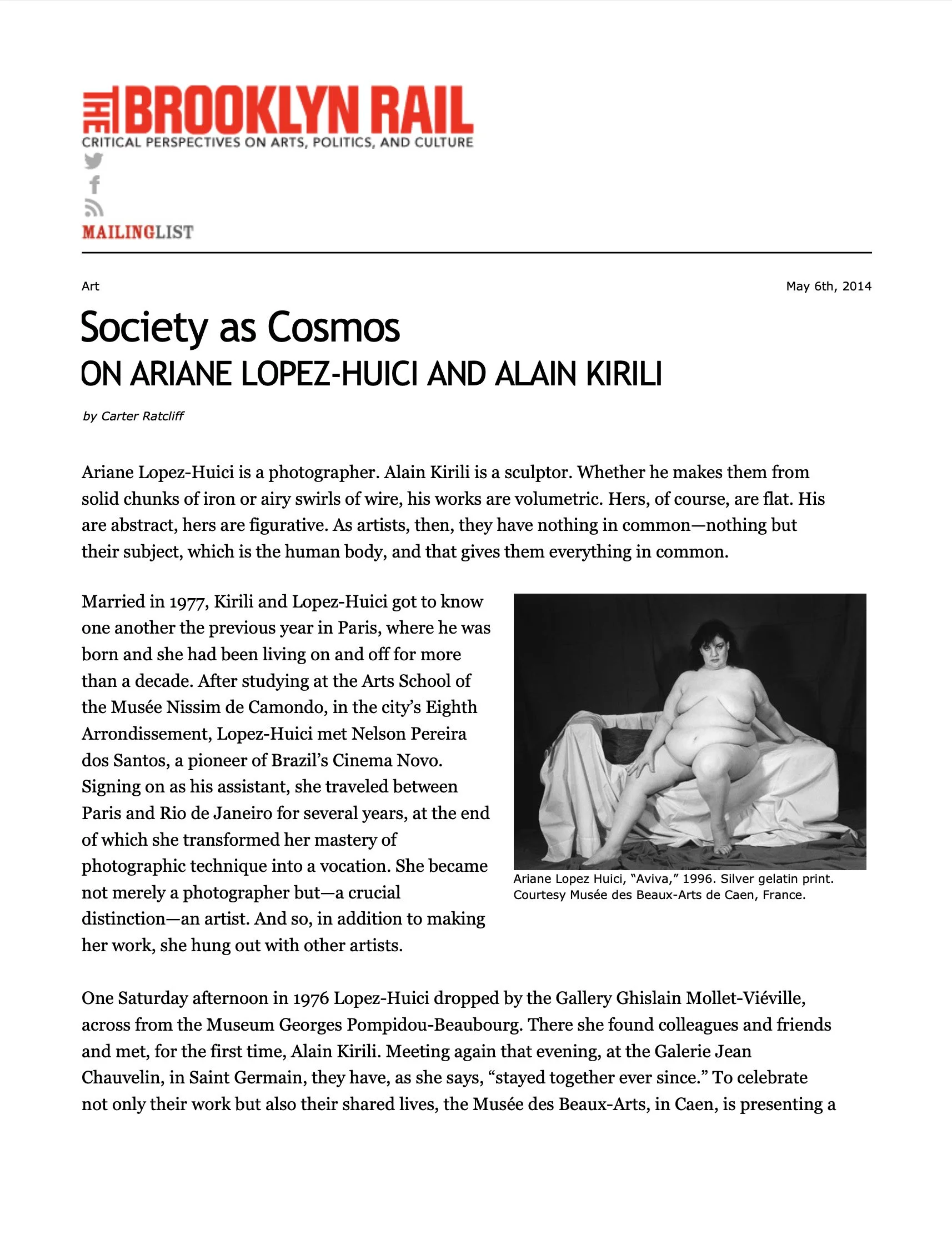

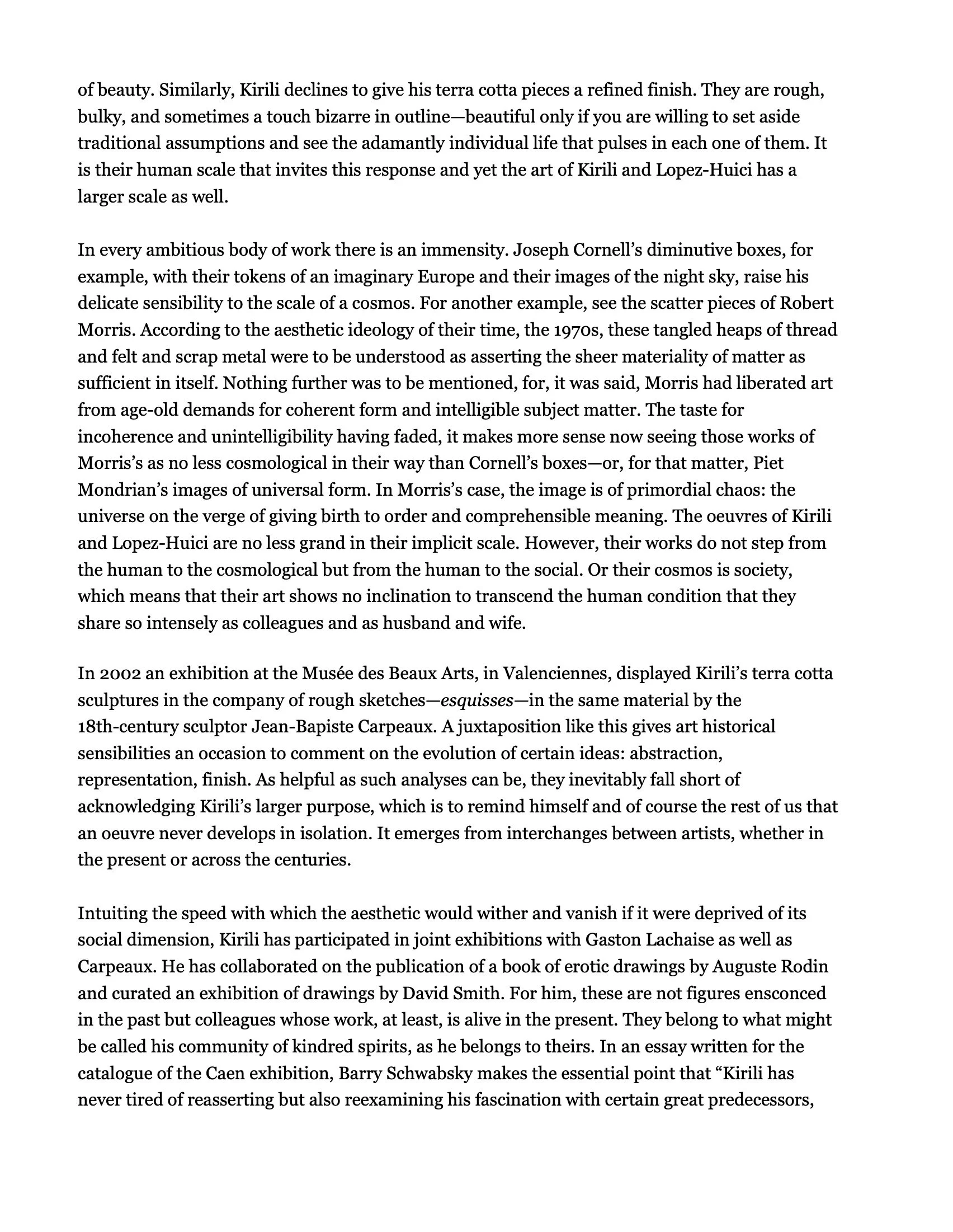

Society as Cosmos

ON ARIANE LOPEZ-HUICI AND ALAIN KIRILI

by Carter Ratcliff

published in the BROOKLYN RAIL, May 6th. 2014

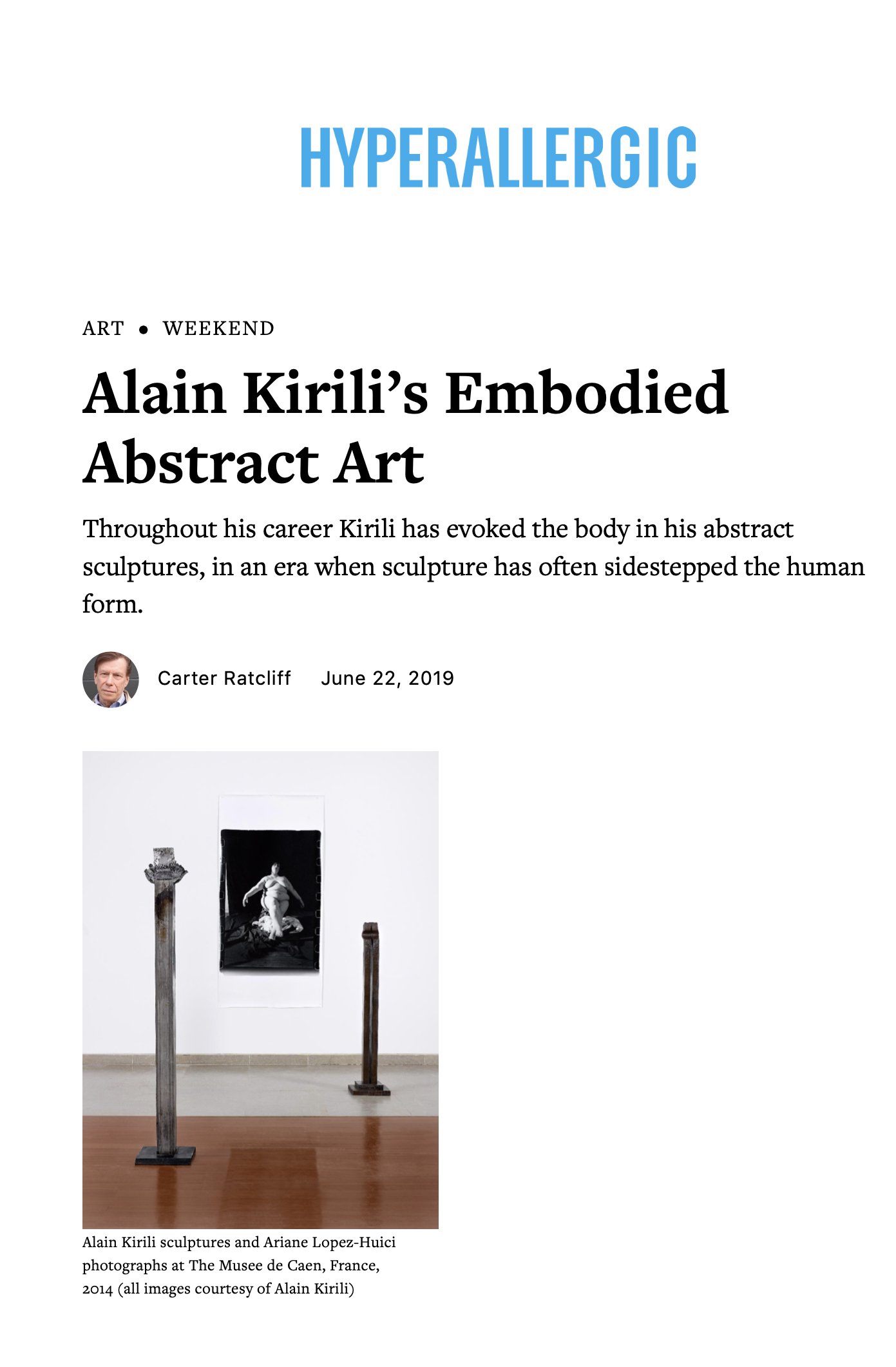

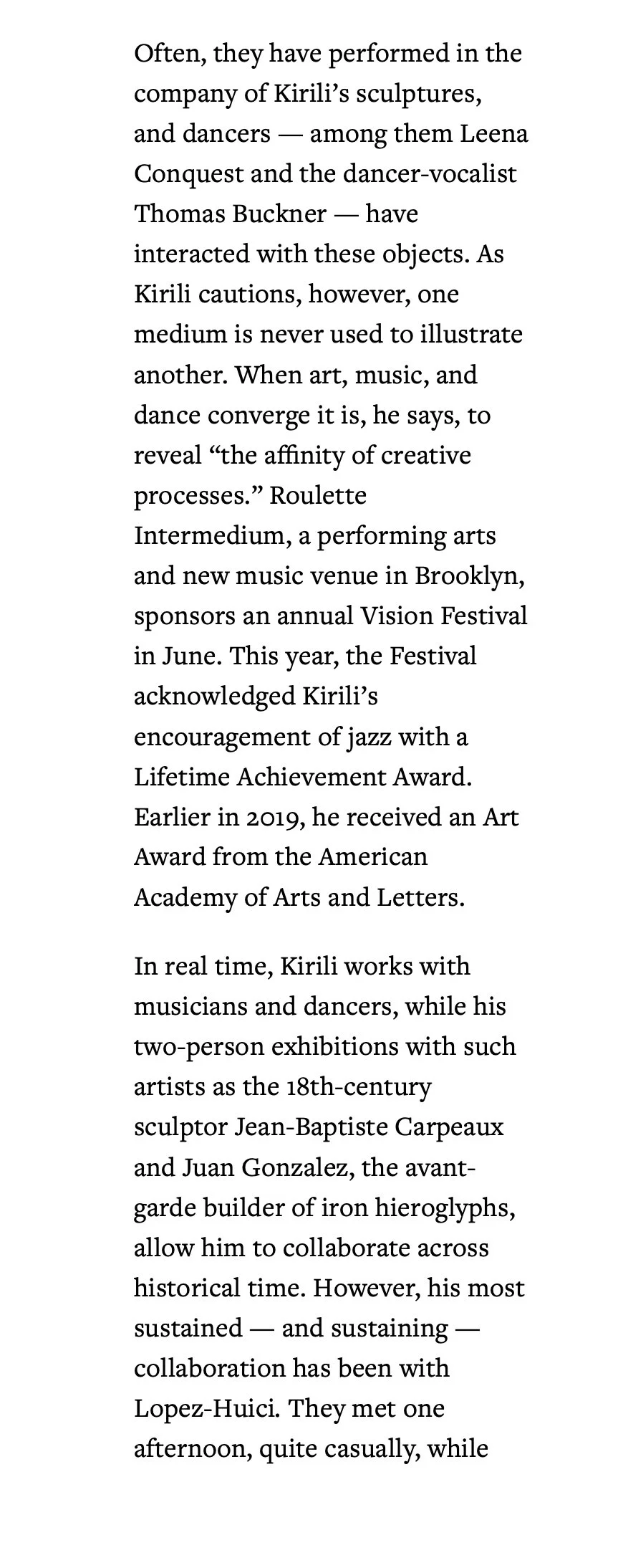

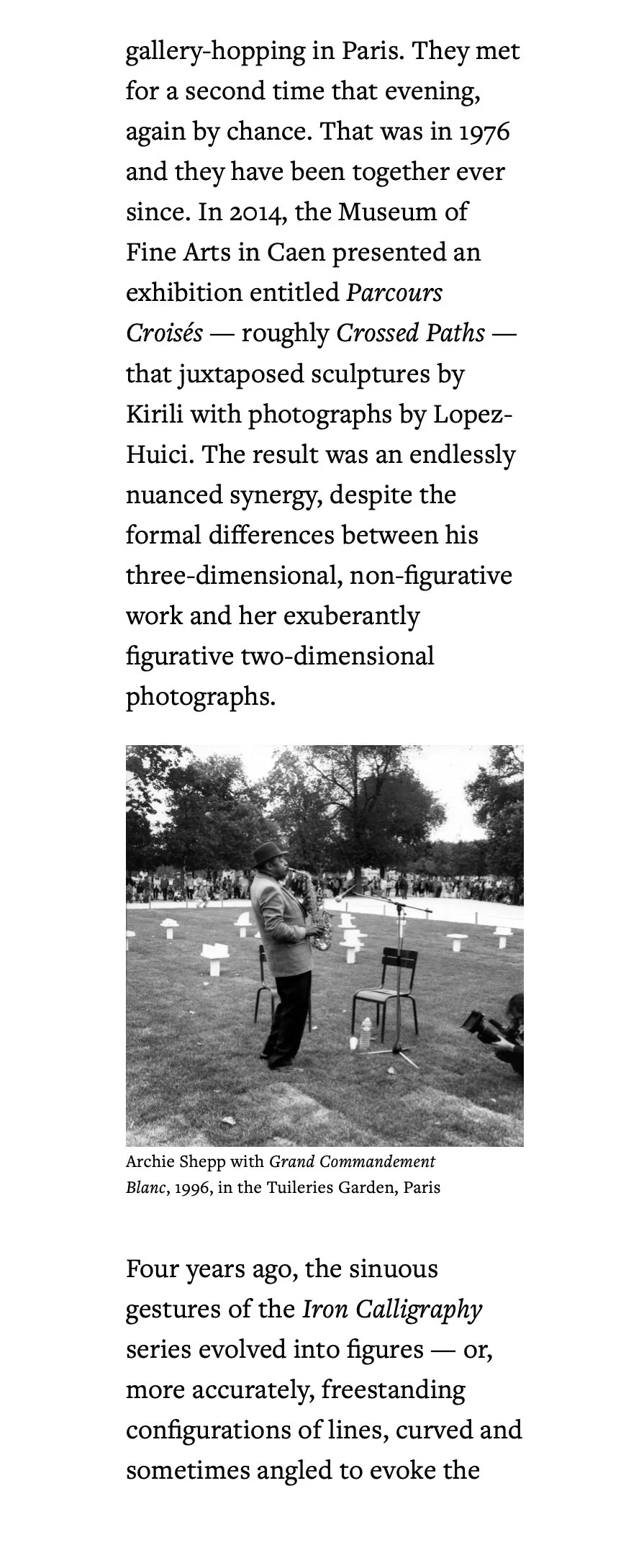

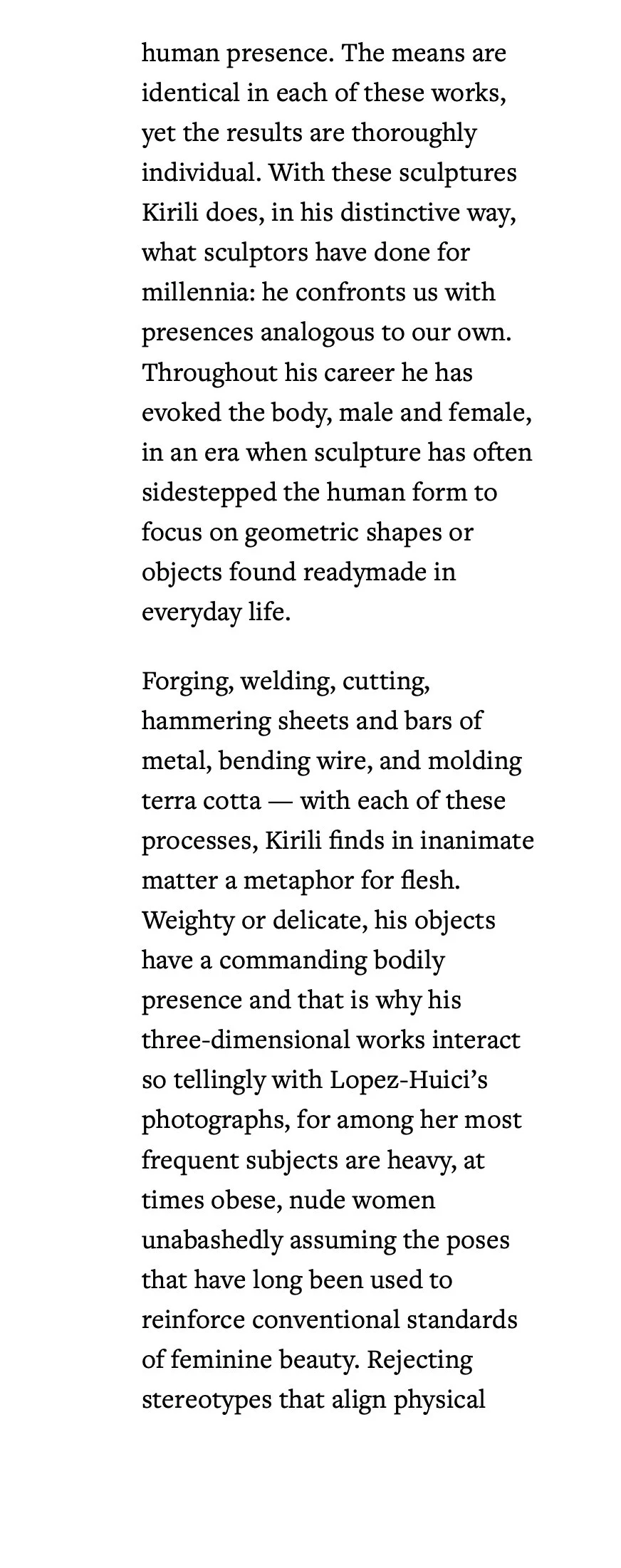

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

Ariane Lopez-Huici, Aviva, 1997, Alain Kirili, Commandement XV, 1991

( photos © Laurent Lecat )

exhibition Parcours Croisés, Musée de Caen, 2014

left : Ariane Lopez-Huici, Shani Ha, 2013, Alain Kirili, Adamah, 2011

right : Alain Kirili, Aria , 2012, Ariane Lopez-Huici, Holly &Valeria, 1998

( photos © Laurent Lecat )

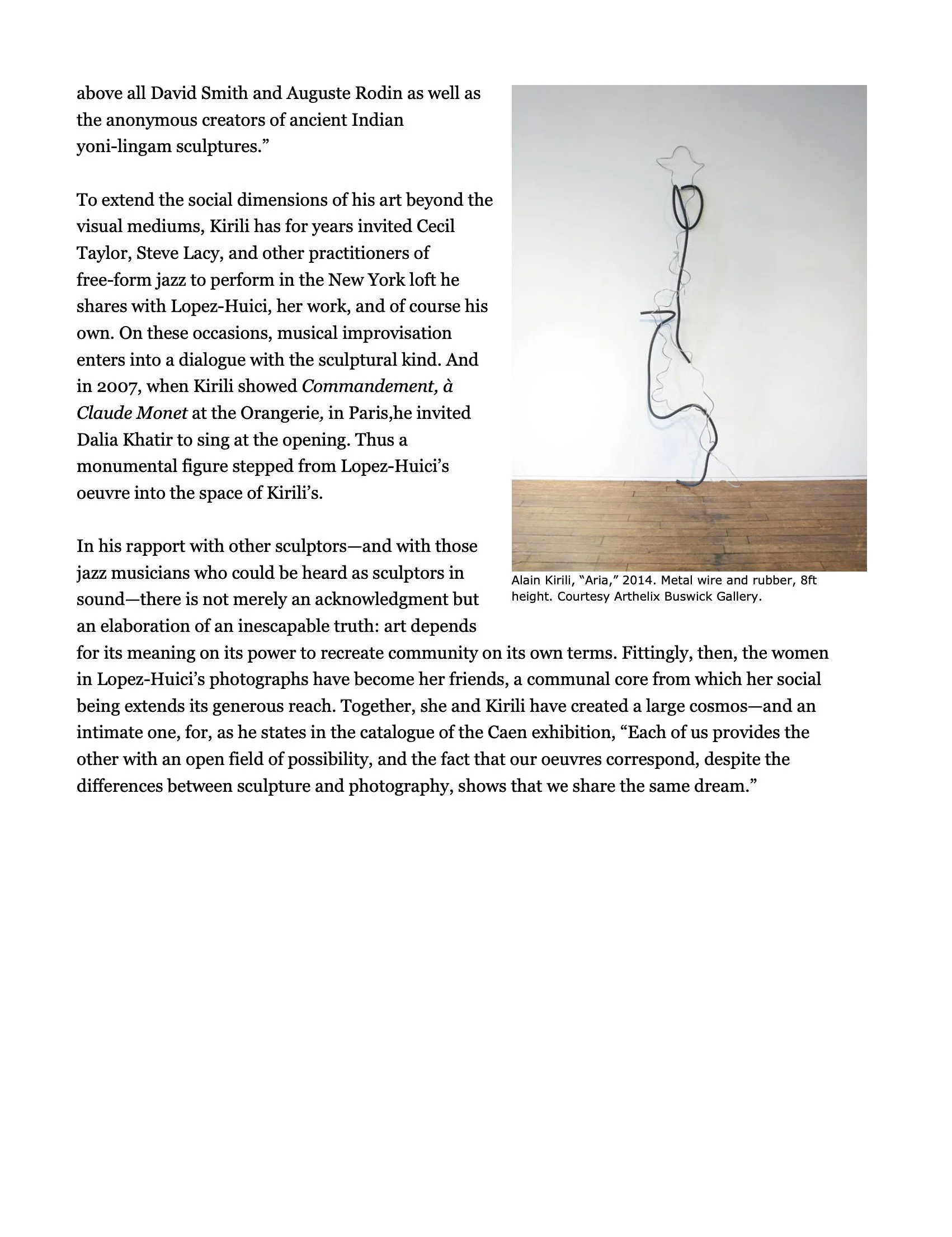

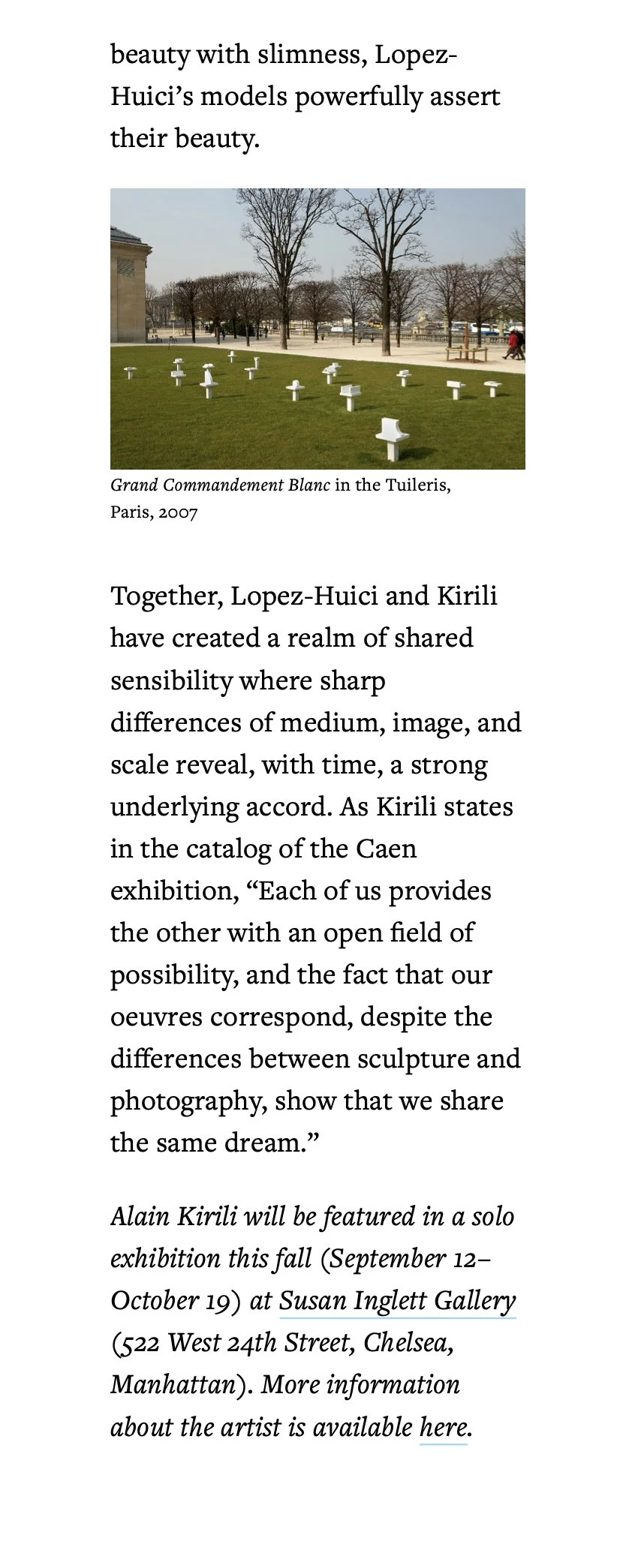

Alain Kirili’s Embodied Abstract Art

by Carter Ratcliff

published in Hyperallergic, june 2019

Carter Ratcliff reading his poetry, White Street Studio, New York, 2015

(Photo © Ariane Lopez-Huici )

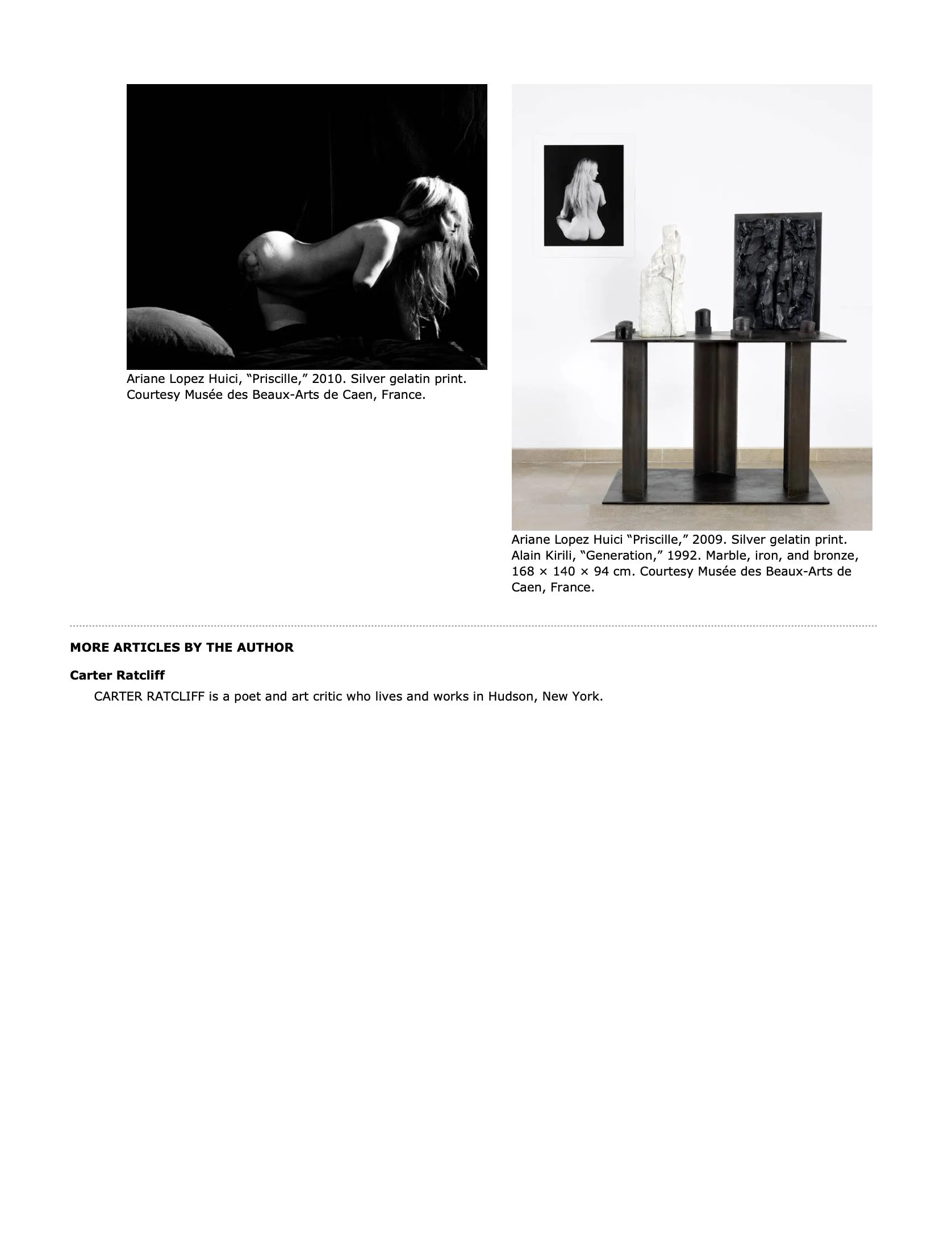

A Tribute to Alain Kirili

a Brooklyn Rail online panel discussion

moderated by Phong H. Bui

featuring Leena Conquest, Francis Greenburger, Maria Mitchell, Robert C. Morgan, Carter Ratcliff, Dorothea Rockburne, Rebecca Smith, Henry Threadgill and more, concluded with a poetry reading by Vincent Katz, October 2021

”A Tribute to Alain Kirili”, a Brooklyn Rail online panel discussion moderated by Phong H. Bui,

featuring Leena Conquest, Francis Greenburger, Maria Mitchell, Robert C. Morgan, Carter Ratcliff, Dorothea Rockburne, Rebecca Smith, Henry Threadgill and more, concluded with a poetry reading by Vincent Katz, October 2021

A Tribute to Alain Kirili (1946–2021)

by Carter Ratcliff

published in A Tribute to Alain Kirili, edited by Robert C. Morgan and Carter Ratcliff,

in The Brooklyn Rail, November 2021

In reading the tributes to Alain, I was happy but not surprised to find such a high degree of unanimity. As his friends say, he was charming, sophisticated, and brilliantly creative. He was generous not only to other artists but to musicians, dancers, and poets. He believed in high culture, not as a marker of superiority but as a down-to-earth good that he and his wife Ariane Lopez- Huici did their part to make available to everyone. Though this is not a complete list of his lovingly remembered virtues and talents, I would like to focus on one that was mentioned only in passing: Alain was an impressively original writer.

In “Statuary versus Idols,” an essay published in Artforum in 1983, he confronts Moses’s prohibition of idolatrous imagery: a Scriptural doctrine potentially troubling not only to Alain and other Jewish artists but to every artist in the Western tradition.

“Really?” you might ask. In a secular art world, who worries about idolatry? Well, Alain did, for he understood that works of art can become fetishes worshipped for their seductive auras of wealth and/or hipness. He did not, however, inveigh against the artwork-as-idol. Instead, he praised artworks— in particular, sculptures by David Smith and Barnett Newman—that have “Presence.” “Statuary versus Idols” revolves around this idea, which is, in his monumental devotion to it, less an idea than an intuited reality. And a red flag to those who lurk on the academic wing of the art world waiting to pounce on any deviation from orthodoxy. For the use of “Presence” with a capital “P” breaks a taboo derived from Jacques Derrida’s argument that the word is the privileged half of a binary opposition built into Western metaphysics in all its patriarchal oppressiveness.

The unprivileged half of this opposition is of course “absence.” Other binaries are nature/culture, mind/body, and speaking/writing. For the tradition that began with the pre-Socratic philosophers and persists even now, these oppositions reflect transcendent truths prior to anything we might say or write about them. For Derrida, they are artifacts of our talking and writing— socio-linguistic “constructs,” and so the process of showing how they work came to be called, aptly enough, “deconstruction.”

Derrida’s aim was anti-authoritarian. Rather than reverse what we might call the power dynamics of these binaries—to privilege “absence,” say, at the expense of “Presence”—he showed that their parts are equal and interdependent. But genuine anti-authoritarianism is a rare thing. The opportunists among Derrida’s followers saw in deconstruction a chance to reconfigure patterns of power and put themselves in charge of the new configurations. Outlawing the word “Presence” by turning it into shorthand for traditional inequities, they condemned anyone who dared to write or utter it. The crucial point is that Alain understood all this, not as a theorist but as a widely read artist with a knack for serious conversation with a wide variety of interlocutors. Thus he wrote admiringly of “Presence” with complete indifference to any tendentious indictment that might be brought against the word.

Underlying this indifference was Alain’s sense that, just as old binaries are not fixed, neither are the meanings of words—a point made by Derrida and, before him, the American pragmatists. Meaning is shaped by contingencies of two kinds: intentions and contexts. In the context Alain and Ariane created for themselves and so many others, you could always be certain that he intended, with everything he did and said, to celebrate possibility, fruition, sensuality—in a word, life. And “Presence” was the accolade he applied to whatever has the peculiarly intense life of matter shaped by a powerful aesthetic intention. He did this in the belief that his audience, everyone from immediate friends to anonymous readers of his essay, would understand the word in the generous way he meant it. This belief showed deep confidence in life’s power to win out over forces of orthodoxy—the intellectual rigidity akin to the puritanism Alain saw as life’s enemy. His confidence was sustained by the courage we find at every stage of his life and of course everywhere in his art. His work didn’t merely have “Presence.” He always put its “Presence” at risk, thereby challenging himself, constantly, to give it new life.